The Guardian: my thoughts on food companies’ taking out the negatives

Here’s my piece from The Guardian, April 2, 2016.

Here’s my piece from The Guardian, April 2, 2016.

Center for Science in the Public Interest has produced a new report:

It’s a lavishly illustrated and well documented investigative report into soda company marketing in developing countries.

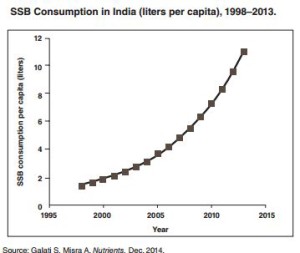

Here’s an example of the documentation, enough to explain why Coke and Pepsi are pouring billions of dollars into bottling plants and marketing in India:

For anyone interested in the nutrition transition from undernutrition to overnutrition in developing countries, this report is a must read. Actually, it’s a must read for anyone who cares about diet and health. If you do nothing else, look at the marketing illustrations from Nepal, Indonesia, or Nigeria. They tell the story on their own.

I’ve just received a new report from USDA’s Economic Research Service, U.S. Food Commodity Consumption Broken Down by Demographics. This looks at trends in per capita food availability—the amounts of specific foods available in the food supply, obtained from data on production and imports, from 1994 to 2008, corrected for waste, per person in the United States.

Food availability data, especially when corrected for waste, suggest trends in per capita consumption patterns (otherwise why would USDA bother to collect them?), but they are not consumption data. They are about supply, not use.

With that said, the trends seem odd to me. They demonstrate a decline in the availability of:

The supply of yogurt and cheese, however, has increased (but their per capita availability is relatively low).

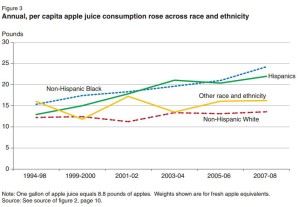

The supply of apple juice also has increased:

Food availability data corrected for waste are supposed to come close to what people actually eat. But if people are eating less of practically all foods, how come so many of us are still gaining weight? Surely it’s not because of apple juice.

These data are an important source of information on U.S. dietary patterns.

But what do they mean? The authors do not say, so it’s left to us to figure that out.

As I keep saying, finding out what people eat is the single most intellectually challenging problem in the field of nutrition.

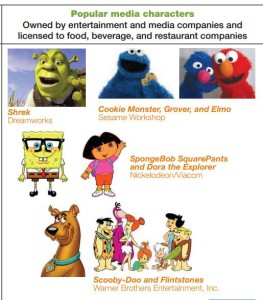

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has a new Issue Brief on food companies’ use of branded characters to market to kids. Here’s what it’s talking about:

These, RWJ says, work better with junk foods than healthy foods, even though some child health advocates have called for their use only for healthy foods.

I don’t want them used to sell anything to kids. I don’t think anyone should be marketing anything to kids.

RWJ’s assessment of the present situation? “Significant opportunities for improvement still exist.”

No kidding.

I’ve just heard about the new Netherlands food guide. It emphasizes sustainability. According to an article in National Geographic’s The Plate,

The Netherlands Nutrition Centre says it is recommending people eat just two servings of meat a week, setting an explicit limit on meat consumption for the first time [but see added comment below].

Here’s what the Netherlands food guide looks like.

Google translator calls this a pyramid, and explains: “Moreover, the Pyramid helps you eat more environmentally friendly broadly.”

Ours, of course, looks like this. I’m guessing the USDA is working on a new food guide in response to the 2015 Dietary Guidelines. These do not mention sustainability at all—the S word.

If you want to check out food guides m other countries, see FAO’s pages on food-based dietary guidelines. You can search the site by regions and countries. Fun!

Added comment: A reader from Amsterdam, who obviously speaks Dutch better than Google translator, and who also is well versed in the Dutch nutrition scene, writes:

Sustainability is indeed an important concern in the new Dutch food guide. However, the recommendation for meat is not ‘two servings per week’, but two servings of red meat and two servings of white meat (chicken), for a total of four per week. One serving is 100 gram or 3.5 oz. of meat. Diehards may add a third serving of red meat; 300 g of red meat (11 oz) plus 200 g of chicken (7 oz) per week is considered the absolute limit.

The fish advice has been reduced from twice to once a week because environmental concerns were thought to outweigh the small health benefit of a second weekly serving of fish.

Why anyone would be opposed to giving healthy food to kids in schools is beyond me, but school food is a flash point for political fights.

Sometimes research helps. Two recent studies produce results that can be used to counter criticisms of government school meal programs.

Kids are eating more healthfully than they used to, according to a research study funded by the Department of Health and Human Services and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The study concludes:

Food policy in the form of improved nutrition standards was associated with the selection of foods that are higher in nutrients that are of importance in adolescence and lower in energy density. Implementation of the new meal standards was not associated with a negative effect on student meal participation. In this district, meal standards effectively changed the quality of foods selected by children.

This is excellent news for proponents of better school food. USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack issued a statement:

This study is the latest in a long list of evidence which shows that stronger school meal standards are leading to healthier habits in schools. Children are eating more fruits and vegetables and consuming more nutrients, making them better prepared to learn and succeed in the classroom. After decades of a growing obesity epidemic that harmed the health and future of our children and cost our country billions, we are starting to see progress in preventing this disease. Now is not the time to take as step backwards in our efforts to do what is right for our children’s health. I urge Congress to reauthorize the child nutrition programs as soon as possible and to maintain the high standards set by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act.

Kids who eat breakfast in school are healthier. Even if they have already had breakfast at home, kids who eat school breakfasts are less likely to be overweight or obese than those who don’t, finds a study from groups at U. Connecticut and Yale.

The findings of the study…add to an ongoing debate over policy efforts to increase daily school breakfast consumption. Previous research has shown that, for students, eating breakfast is associated with improved academic performance, better health, and healthy body weight. But there have been concerns that a second breakfast at school following breakfast at home could increase the risk of unhealthy weight gain.

So now we know: they do not.

Research like this is unlikely to settle the matter but it ought to help school personnel who are working hard to make sure that kids get something decent to eat and to move ahead on school food initiatives.

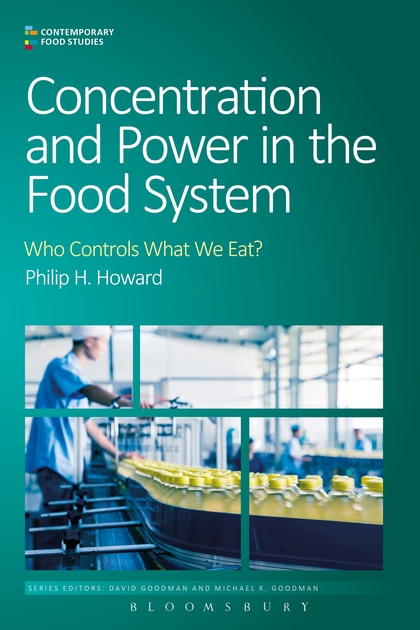

I don’t know Philip Howard personally but I have long appreciated his graphic visualizations of the extent of concentration—only a few companies owning fast percentages of the market—in various industries:

This brief book summarizes his work in developing these graphics and makes it clear why he thinks industrial concentration is a problem for American democracy. Without competition, these companies get away with doing whatever they want. He gives a few examples:

Walmart, which controls 33 percent of US grocery retailing, is challenged for exploiting its suppliers, taking advantage of taxpayer subsidies, and paying extremely low worker wages…Monsanto, which controls 26 percent of the global commercial seed market, is denounced for its influence on government polocies, spying on farmers it suspects of saving and replanting seeds, and the environmental impacts of herbicides tied to these seeds. These impacts tend to disproportionately affect the disadvantaged—such as women, young children, recent immigrants, members of minority ethnic groups, and those of lower socioeconomic status—and as a result, reinforce existing inequalities…Like ownership relations, the full extent of these consequences may be hidden from public view.

Howard’s solution? The food movement!

Joining these movements and supporting the alternatives created by others could therefore be essential to maintaining our ability to feed ourselves in the future.

The book is fun to read (“seed-industrial complex”) and, obviously, well illustrated. If you want to know how current-day food markets really work, this is the place to start.

One of the newsletters I subscribe to, BeverageDaily.com, has a special edition—a collection of its articles—on what the industry is doing to address its biggest problem: reducing sugar.

What is the beverage industry doing to cut calories?

Health and wellness is at the forefront of consumers’ minds, and sugar gets plenty of bad press. Obesity is as big a concern as ever, and soft drinks are in the firing line.

What is the beverage industry doing to reduce calories? How are market leaders reformulating and revamping their portfolios; and what healthier brands are appearing?

From alternative sweeteners to packaging sizes, we look at what the industry is doing to cut calories – and how well these initiatives are working.

From reformulation to nutritional labeling, the non-alcoholic beverage industry has adopted a variety of strategies to reduce the calorie content of drinks. We look at how different strategies from around the world are being implemented. .. Read

You can see why the industry has a problem. Sugar tastes good. These other things not so much.

Americans these days don’t want artificial and unsustainably produced ingredients in the food they buy and eat. For the makers of highly processed foods – ultraprocessed in today’s terminology – there isn’t a lot that they can do to make the products appear fresh and natural.

But Campbell’s is certainly trying. A few months after announcing that it will phase out genetically modified organisms (GMOs), the iconic soup company said on Friday that it will remove Bisphenol-A (BPA) from its cans by next year.

BPA, you will recall, is a chemical typically used in polycarbonate plastic containers and in the epoxy linings of food cans. It’s also an endocrine disrupter, which means it can interfere with the work our hormones are doing. Some research finds BPA to have effects on childhood development and reproduction.

Although the FDA doesn’t believe evidence of potential harm is sufficient to ban BPA from the food supply, the agency discourages use of BPA-polycarbonate or epoxy resins in baby bottles, sippy cups or packaging for infant formulas. For the past year or so, other retailers have been working hard to phase out BPA and to reassure customers that their cans and packages are safe.

All of these companies sell highly processed foods in an era when the public is demanding – and voting with their dollars – for fresh, natural, organic, locally grown and sustainably produced ingredients.

They can’t provide those things, but they can tout the bad, or unpopular, things that aren’t part of their product, the “no’s”: no unnatural additives, no artificial colors or flavors, no high fructose corn syrup, no trans fat, no gluten and, yes, no GMOs or BPA.

Let me add something about companies labeling their products GMO-free. In my view, the food biotechnology industry created this market – and greatly promoted the market for organics, which do not allow GMOs – by refusing to label which of its products contain GMOs and getting the FDA to go along with that decision. Whether or not GMOs are harmful, transparency in food marketing is hugely important to increasing segments of the public. People don’t trust the food industry to act in the public interest; transparency increases trust.

Vermont voted last year to mandate GMO labeling in the state – the US Senate rejected a bill in mid-March attempting to undermine it – and food conglomerates such as Campbell’s, General Mills, ConAgra, Kellogg and Mars have committed to labeling their products as containing GMO.

In addition to removing BPA from packaging and GMO from products, at least 11 other companies have announced recently that say they are phasing out as many artificial additives as possible, as quickly as they can.

Taco Bell, for example, will get rid of Yellow Dye #6, high fructose corn syrup, palm oil and artificial preservatives, and replace them with “natural” ingredients. Huge food companies such as Kraft, Nestlé (no relation) and General Mills are heading in the same direction.

All this may well benefit consumers to an extent. It also makes perfect sense from a business perspective: the “no’s” sell. But what everyone needs to remember is that foods labeled “free from” still have calories and may well contain excessive salt and sugars. The healthiest diets contain vegetables and lots of other relatively unprocessed foods. No amount of subtraction from highly processed foods is going to change that.