Yes! The Berkeley soda tax is doing what it is supposed to

Jennifer Falbe and other investigators from Kristin Madson’s group at UC Berkeley have just produced an analysis of the effects of the Berkeley soda tax on consumption patterns.

They surveyed people in low-income communities before and after the tax went into effect. The result: an overall 21% decline in reported soda consumption in low-income Berkeley neighborhoods versus a 4% increase in equivalent neighborhoods in Oakland and San Francisco.

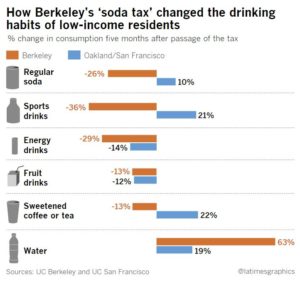

The Los Angeles Times breaks out these figures:

In Oakland and San Francisco, which have not yet passed a tax, sales of regular sodas went up by 10%.

Other findings, as reported by Healthy Food America:

- During one of the hottest summers on record, Berkeley residents reported drinking 63 percent more bottled water, while comparison cities saw increases of just 19 percent.

- Only 2 percent of those surveyed reported crossing city lines to avoid the tax.

- The biggest drops came in consumption of soda (26%) and sports drinks (36%).

Agricultural economist Parke Wilde at Tufts views this study as empirical evidence for the benefits of taxes. He writes on his US Food Policy blog that it’s time for his ag econ colleagues to take the benefits of taxes seriously:

There is a long tradition in my profession of doubting the potential impact of such taxes…Oklahoma State University economist Jayson Lusk, who also is president of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association (AAEA), has blogged several times about soda taxes, agreeing with most of the Tamar Haspel column in the Washington Post, and concluding stridently: “I’m sorry, but if my choice is between nothing and a policy that is paternalistic, regressive, will create economic distortions and deadweight loss, and is unlikely to have any significant effects on public health, I choose nothing” (emphasis added).

Wilde points out that Lusk has now modified those comments in a blog post.

All that said, I’m more than willing to accept the finding that the Berkeley city soda tax caused soda consumption to fall. The much more difficult question is: are Berkeley residents better off?

Yes, they are.

The Berkeley study is good news and a cheery start to the week. Have a good one.

Addition

Politico adds up the “piles of cash” being spent on the soda tax votes in San Francisco, Oakland, and Alameda and analyzes the soda industry’s framing of the tax as a “grocery tax.”