Food-Navigator-USA’s special edition on food labeling and litigation

This is one of FoodNavigator-USA’s special edition collections of articles on similar themes, in this case food labeling and lawsuits over labeling issues. These are a quick way to get up to speed on what’s happening from a food industry perspective . FoodNavigator introduces this collection:

Food and beverage companies have faced a tsunami of false advertising lawsuits over the past five years. But how big of an issue is this for the industry, who has been targeted, and what strategies are working, both for plaintiffs and defendants in these cases? In this special edition, we also look into labeling issues and trends, from healthy, Paleo and grass-fed claims to NuTek’s potassium salt petition.

- FOOD LITIGATION 101: Are you up to speed? There have been hundreds of class action lawsuits directed against food and beverage companies in recent years over everything from evaporated cane juice to Non-GMO claims. But has the false advertising litigation trend peaked, and if not, what are the new areas of vulnerability for food companies? .. Read

- More farm-related claims to appear on pack, Innova Market Insights forecasts: Now that clean label has moved on from being a trend to becoming “the new rules of the game,” Innova Market Insights predicts more brands will rely on ‘farm to fork’ claims and bucolic imagery as a differentiator… Read

- Paleo certification requests have doubled annually, scheme embraced by ‘household names,’ says Paleo Foundation: Demand for Paleo-certified products are on the rise. But is the diet – and the certification scheme – based on sound science? We chat with Paleo’s critics and proponents to get the inside scoop… Read

- Dairy from cows fed GM feed is not ‘all-natural’, alleges lawsuit vs Dannon – but will it fly? Has the FDA’s probe into ‘natural’ claims on food labels put a stop to the tidal wave of false advertising lawsuits engulfing food manufacturers? Not if a new complaint against Dannon is anything to go by, which also delves into the thorny issue of GMOs, another area currently being scrutinized by regulators. .. Read

- Future of Nutrition Facts, menu labeling & food safety are unclear under Trump, CSPI says: While President-elect Trump’s position on food policy is relatively unclear still, changes to the exhaustively researched and intensely debated Nutrition Facts label, menu labeling rule and food safety regulations could all be on the chopping block under the new administration, warns a top nutrition policy expert… Read

- Comments in FDA docket reveals consumers’ shifting perceptions of ‘healthy’: If the FDA’s decision to wade into the ‘natural’ debate seemed like an act of sadomasochism, its decision to re-examine the criteria underpinning ‘healthy’ claims on food labels looks set to be equally painful, judging by the first wave of public comments filed in the docket… Read

- FDA hints at how conventional foods can make structure/function claims: For the first time, FDA weighs in on what marketers must have on hand to support claims about conventional foods’ direct impact on consumers’ bodies. .. Read

- Soup-To-Nuts Podcast:The rise & future potential of grass fed claims: Grass-fed claims on products are a beacon for consumers who are health-conscious, want minimally processed food and care about animal welfare, and as such manufacturers increasingly are using them on products across categories and channels to drive up sales sharply… Listen now

- ProTings closes $1.2m financing round, changes name to Protes after spat with Original Tings: Brooklyn-based pea protein chip pioneer Proformance Foods has closed a $1.2m financing round led by a leading CPG company, and changed its brand name from ProTings to Protes following a trademark dispute with B&G Foods, which owns the Original Tings brand… Read

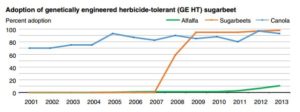

- Vox Pop: Consumers had this to say about GMO labeling…On the heels of President Barack Obama signing into law a federal bill requiring the disclosure of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) on packaged food and beverage products, we at Beverage Daily and FoodNavigator-USA asked consumers at a downtown Chicago farmers market what they thought of GMOs… Watch now

- Are ‘GMO-free’ (as opposed to ‘non-GMO’) claims legally defensible? As the Non-GMO Project states on its website, ‘GMO-free’ claims are “not legally or scientifically defensible due to limitations of testing methodology” coupled with cross-contamination risks. In future, however, that could change as testing methods become more sophisticated, predicts Clear Labs, a Californian start-up which recently hit the headlines after identifying human and rat DNA in hamburgers [albeit within safe parameters]… Read

- Label Insight: Your SmartLabel landing pages could become more important than your website or facebook pages: While the SmartLabel initiative has been dismissed by some as an elaborate conspiracy by big food companies to avoid mandatory on-pack GMO labeling statements, it will ultimately have far broader significance – and potentially a huge impact on how consumers view all food and beverage products – predicts product data and image platform Label Insight… Read

- House approves federal GMO labeling bill that nullifies Vermont law: The US House of Representatives has voted to pass a federal GMO labeling bill (306:117 votes) that would pre-empt and nullify all state-led GMO labeling laws including the one that has just come into effect in Vermont. .. Read

- Hampton Creek to settle worker classification lawsuit: Just Mayo maker Hampton Creek – one of a growing number of food companies sued for allegedly misclassifying workers as independent contractors as opposed to employees – is settling its case in order to avoid the hassle and expense of protracted litigation, court documents show… Read

- Kellogg, Post & General Mills urge courts to toss ‘meritless’ sugar lawsuits: Kellogg, General Mills and Post Foods have urged the courts to ditch high-profile lawsuits over the sugar content in their cereals, on the grounds that their claims are pre-empted by federal law and that no reasonable consumer would find their labels to be false or misleading… Read

- Dole Foods 9th Circuit ruling reignites all-natural lawsuit, ’emboldens plaintiff’s bar’: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has reversed (in part) a lower court’s ruling that Dole Foods’ ‘all natural fruit’ labeling likely isn’t deceptive, resurrecting a four-year-old lawsuit, and giving fresh ammunition to plaintiff’s attorneys pursuing ‘all-natural’ cases… Read

- Parties clash over Welch’s ‘made with real fruit’ fruit snack label claims: Reasonable consumers may well be misled by the packaging of Welch’s fruit snacks, a magistrate judge has concluded, prompting a lengthy rebuttal from the defendants in court documents filed this month. .. Read

- Shoppers aren’t confused by our labels, Chobani tells court: ‘Plaintiffs count on a consumer who is a veritable fool’: A false advertising lawsuit alleging that Chobani’s labels are confusing and deceptive, paints American consumers as credulous fools unable to apply common sense when they go shopping, argues the yogurt maker in court documents urging the judge to toss the case… Read

- GMA to FDA: Sodium reduction guidance must be re-worded or industry will face a tidal wave of ‘frivolous litigation’: Two years isn’t enough time for food manufacturers to make the kind of reductions in sodium that the FDA is asking for, says the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), which also urges the agency to tweak the wording of its guidance in order to avoid “a wave of frivolous litigation.”.. Read

- American Bakers Association backs ‘potassium salt’ petition: It sounds more clean label: The American Bakers Association (ABA) has joined the CSPI, Unilever, and other food manufacturers in voicing its support for a citizen’s petition asking the FDA to permit ‘potassium salt’ as an alternate name for potassium chloride on food labels, while the Salt Institute remains resolutely opposed… Read