I am an advisor to the American Society of Nutrition’s Early Career Nutrition group and was asked to address this question for its spring/summer newsletter (my piece starts on page 9). Here’s what I said:

As a newly appointed advisor to ASN’s Early Career Nutrition (ECN) group, I am pleased to be asked to explain why I do not think it a good idea for nutrition scientists, practitioners, and societies to be funded by food, beverage, and supplement companies (collectively, the food industry) for research that is in any way related to their products. If we do, we run the risk of appearing as if our interests are conflicted. More than that, we risk being conflicted—influenced to be less critical or silent about nutrition issues related to the donor’s products. There is no getting around it: whatever the reality of the relationship, taking money from a for-profit food company makes us appear to be supporters of whatever products the company sells.

I worry a lot that financial ties between food companies and ASN tarnish its reputation and ours. It troubles me when critics outside our profession view us as “on the take” and publish reports exposing ASN’s financial ties to companies that have a marketing stake in what we study or say about their products. When ASN meetings are sponsored by food companies, it makes these financial ties seem normal. ASN provides a platform for industry-sponsored sessions such as the one this year on the benefits of Stevia, but you can bet they don’t include speakers who might say anything critical. Sponsorship excludes that possibility.

Most of what we know about the effects of sponsorship comes from a very large body of research on funding by the cigarette, chemical, pharmaceutical, and medical device industries. The results of this research are remarkably consistent: they demonstrate that industry funding influences the design, interpretation, and outcome of research. Nutrition is late to this type of investigation, but several recent studies show that studies funded by the food industry almost invariably favor the interests of the sponsor. Publication bias against negative studies explains only a small part of these findings.

Industry funding of nutrition research is an important issue where there are diverse opinions. ASN is a welcoming place encouraging discussion from members with all perspectives on topics including this one. ASN members share a common unifying goal of advancing nutrition science to promote the public welfare. Working together we can and we will continue to disclose potential conflicts of interest and advance the field for the public benefit. Dr. Mary Ann Johnson, ASN President

Investigators who take such funding insist that it has no effect on the design, conduct, interpretation, or publication of their research. This insistence is consistent with another large body of research demonstrating that gifts have a profound influence on attitudes, behavior, and action–but that recipients are blind to these effects. The medical literature shows that even small gifts—pens and pads—are enough to influence prescription practices, and that larger gifts have even greater effects. But the influence occurs below the radar of critical thinking. It is unintentional, unconscious, and unrecognized.

What most troubles me is the lack of questioning of industry penetration into our societies and research. I think we should be raising questions about ASN’s involvement with companies whose profits might be affected by our opinions or research results. Should ASN have competed to manage the industry-funded Smart Choices program that ended up putting a seal of approval on Froot Loops? Does it make sense for ASN to endorse public policy statements promoting the benefits of processed foods or opposing “added sugars” on food labels? Is it reasonable for ASN to argue on social media that it is inappropriate to question industry funding of research? Must ECN sessions at the annual meeting really be funded by companies such as PepsiCo (last year) or Abbott Laboratories? These actions send the message that ASN is an arm of the food industry and that we uncritically support what it makes, sells, or does.

But let’s turn to a more immediate concern: research funding. As early investigators, you face intense pressures to bring in external grants to pay for your studies, overhead, and maybe even your salaries. Government funding for many areas of nutrition research is declining. These pressures are real. But just as real are the effects of industry funding on research.

From March 2015 to March 2016, I posted summaries of industry-funded studies on my blog. During that year, I collected 168 studies. Of these, 156 yielded results favoring the sponsor’s interests. I only could find 12 studies that did not. This was a casually collected convenience sample but it did allow one conclusion: it is easier to find industry-funded studies with positive results than those with negative results. Nevertheless, recent systematic studies come to the same conclusion. Studies funded by Coca-Cola, for example, are far more likely to conclude that its products have no effect on obesity or type 2 diabetes than do studies funded by government or foundations.

Because we are generally unconscious of the influence of financial ties, it is easy for us to deny the influence or argue that nonfinancial interests—preferences for hypotheses and desires for career advancement–are just as biasing. Yes they may be biasing, but all scientists have them. In contrast to financial ties to industry, it is not possible to eliminate nonfinancial biases and still do science.

I am often asked whether there is a way to take money from food companies and maintain intellectual independence and professional reputation. I regret that I cannot think of any viable way to do that. The ASN has appointed a “Truth” commission to examine this issue and I look forward to its report. In the meantime, I am hoping that you will give thought to the potential conflict of interest and reputational loss that you risk with food industry ties. You must figure out for yourself whether you think the risks are worth taking.

If you do decide to engage with industry, you will need to disclose it. Most journals now require authors to reveal who pays for their work, but even when done diligently, disclosure is not sufficient to alert readers to the extent to which industry funding influences research outcome and professional opinion. Yes, disclosure is uncomfortable, perhaps explaining why so many studies identify frequent lapses. It is likely to become more uncomfortable. In response to a petition from the Center for Science in the Public Interest (which I co-signed), the National Library of Medicine has announced that it will henceforth add funding disclosures and conflict-of-interest statements to PubMed abstracts.

It is only fair to tell you how I handle these issues. My disclosure statement says:

Dr. Nestle’s salary from NYU supports her research, manuscript preparation, Website, and blog at https://foodpolitics.com. She also earns royalties from books and honoraria from lectures to university and health professional groups about matters relevant to this topic.” I also on occasion speak to food industry groups. When I do, I accept reimbursements for travel expenses but ask that honoraria be donated to the NYU library’s food studies collection.

This policy, imperfect as it may be, is the best I can do. I ask only that you think seriously about these issues and figure out for yourself how best to deal with them. I am happy to discuss these matters and am most easily reached at marion.nestle@nyu.edu.

References

- Nestle M. Food company sponsorship of nutrition research and professional activities: A conflict of interest? Public Health Nutrition 2001;4:1015-22.

- Nestle M. Corporate funding of food and nutrition research: science or marketing? JAMA Internal Medicine 2016;176(1):13-4.

- Krimsky S. Science in the Private Interest: Has the Lure of Profits Corrupted Medical Research. Rowman and Littlefield, 2004.

- Lo B, Field MJ, eds. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- Simon M. Nutrition Scientists on the Take from Big Food. Eat Drink Politics and the Alliance for Natural Health, Jun 2015.

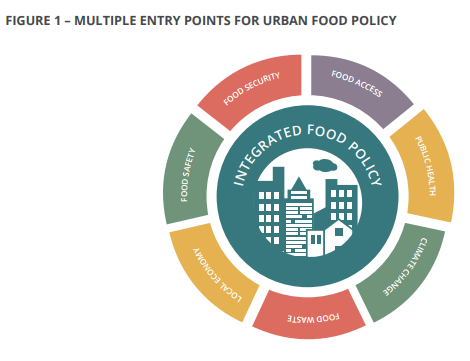

And it is highly instructive about what has to be in place to put these policies in action (the report calls them enablers).

And it is highly instructive about what has to be in place to put these policies in action (the report calls them enablers).