The world now experiences two forms of malnutrition which may seem contradictory: “undernutrition” (which includes micronutrient deficiencies) and “overnutrition” (obesity and its health consequences).The problem of malnutrition in developing countries is approached by most aid bodies (donors, international organisations and NGOs) and governments solely from the angle of undernutrition. And yet in these countries, the complex and multi-faceted challenge which malnutrition now presents can justifiably be called the double burden of malnutrition. In addition to the continuing problem of undernutrition there are now major issues linked to overnutrition and its associated illnesses.

Rapid nutrition transition

The stereotyped image of skeletal young children with protruding bellies saved by souls of goodwill in sub-Saharan Africa is still too widespread. Severe acute malnutrition still persists of course, especially among the victims of extreme poverty, natural catastrophes and wars. Naturally, this deadly disease must continue to be addressed and treated, as numerous NGOs are doing.

The treatment of malnutrition should focus not only on severe malnutrition in children. Less severe malnutrition, going back to life in the foetus and resulting from malnutrition in women even prior to their pregnancy, continues to contribute to stunting, which affects 23.8% of all children under the age of 5 throughout the world.

In parallel with acute and chronic undernutrition, the “nutrition transition” in low-income countries, driven by globalisation, urbanisation and technological progress and linked to “overnutrition,” leads to a swift increase in obesity and other chronic diseases – mainly diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Nutrition transition is the term used to describe the progressive Westernisation of eating patterns, typified by a sharp increase in the consumption of animal fats and processed foods all over the world, combined with an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. It is easy to see how this transition encourages the increase in overweight and obesity.

Today, undernutrition alone is not the major issue; the greatest problem is the double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition. According to estimates from 129 countries with available data, 57 experience serious problems of both undernutrition in children and overweight in adults[i]. And Africa is not exempt from this double burden where undernutrition and overweight are undeniably linked. In West Africa, 50% of women of child-bearing age are anemic while at the same time 38% are overweight and 15% are obese. For the whole of sub-Saharan Africa, 40% of children have stunted growth characteristic of chronic undernutrition, while 7.5% of adults suffer from obesity. Malnutrition early in life increases the subsequent risk of chronic diseases in places where obesity is encouraged by the environment. Obesity is now on the increase among children in all developing countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that between 1990 and 2015 the number of overweight or obese African children doubled from 5 to 10 million.

The responsibilities of the industrial food system

It is often said that communication aimed at changing food habits is the best way to prevent obesity, a problem reserved for rich people in low-income countries. This cliché contains three errors:

- The first is the claim that preventing nutrition-related chronic relies entirely on the capacity of individuals to make appropriate choices regarding food, physical activity or lifestyle. This claim ignores the well-documented effects of the food system and the socio-cultural factors which play a determining role and which influence the choice of individuals.

- The second error is to believe that significant changes cannot be made to the eating practices of limited-income groups in the absence of an increase in resources. Yet several studies show the opposite, whether they are about exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and improved complementary feeding, or else hygiene measures and supplies of drinking water.

- The third error is to consider that obesity continues to be only a problem of the rich in low-income countries. Obesity is escalating and affecting growing numbers of not so well-off people, particularly in cities.

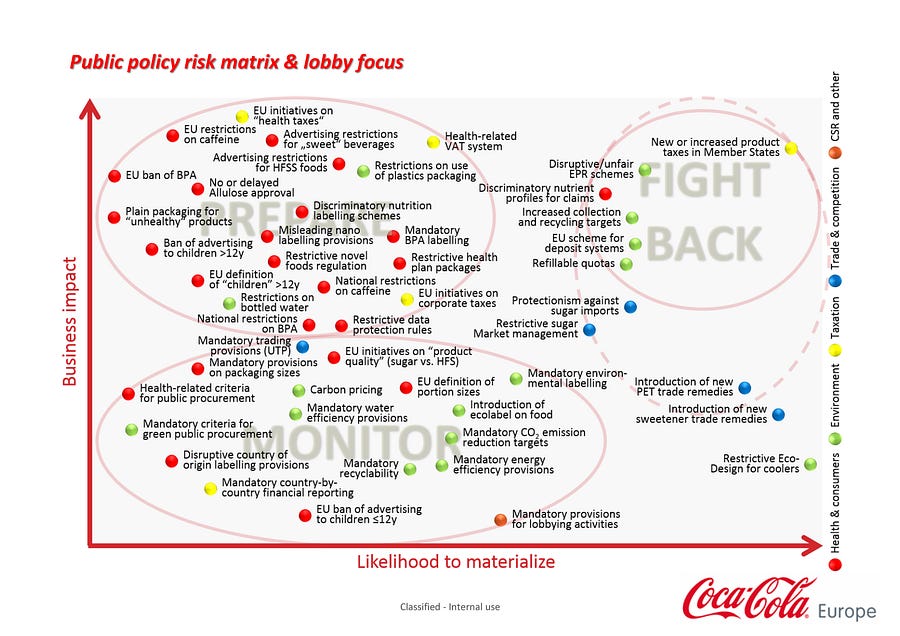

When analysing the impact of the food system, it is necessary to account for the agri-food industry (Big Food). On a world-wide scale Big Food is primarily responsible for the “nutrition transition” towards processed food. “Globalised” industrial food is gradually replacing traditional cooking and locally produced foods, with ultra-processed foods’ (food-like substances as Michael Pollan calls some of them) undeniable appeal for city-dwellers and young people as these products are strongly associated with Western-style fast food and heavily promoted by the media. This appeal is reflected in profound changes in consumption trends in developing countries. Global sales of highly processed foods increased by 44% from 2000 to 2013, but only by 2% in North America as opposed to 48% in Latin America and 71% in Africa and the Middle East.

So what is the problem? Industrial food products (and drinks) are often a nutritional disaster: rich in calories, sugar, fat and salt, but low in essential nutrients and fiber. Even more, these products are relatively inexpensive, often less expensive than more nourishing local food products.

Changing the food environment

What is the explanation for the popularity of these “globalized” food products? Part of the answer lies in extremely effective advertising. Anyone travelling in Africa, for example, will see campaigns to promote salty stock cubes to replace traditional spices and vegetables. “Social marketing” efforts to change eating behaviour must be as forceful as these adverts, with commensurate budgets.

One idea is to impose a tax on soft drinks or other highly processed foods and use the revenues to finance cutting-edge nutrition education campaigns. This is what the United Kingdom has recently decided to do by taxing soft drinks.

It is especially important to rethink the nutrition programs created by NGOs and financed by international aid. Correcting the nutrition of malnourished mothers or children is only part of the problem.

A wider vision is needed to recognize the threat to world health posed by nutrition-related chronic diseases.

To cope with this new challenge, it will be important to address many determinants of health – education, social disparities, housing, and culture – as well as the food environment. The latest report on global nutrition1 points out the excellent return on investment of nutrition interventions (16 for 1), and challenges governments and decision-makers to identify and implement strategies that target the double burden of malnutrition. If this is not done, it will be difficult to reach the nutrition objectives set by the WHO for 2025 (see below). Solutions do exist, however, as can be seen from places such as Ghana, Brazil, or the state of Maharashtra in India, which have had encouraging results in fighting malnutrition in all its forms.

Global nutrition targets for 2025

- Reduce the number of children with stunted growth by 40%

- Reduce and keep the prevalence of acute malnutrition in under-five children (low weight) under 5%

- Avoid any increase of overweight in children

- Reduce the prevalence of anemia in women of child-bearing age by 50%

- Increase exclusive breastfeeding for babies less than 6 months old by 50%

- Reduce low birth weights by 30%

- Avoid any increase in the prevalence of overweight, obesity and diabetes in adults.

The opinions expressed on this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of their institutions or of AFD.

[i] Global Nutrition Report 2016 www.globalnutritionreport.org