Menus, San Francisco Style

Grant Street, Chinatown, October 11, 2017

Grant Street, Chinatown, October 11, 2017

I did a blurb for this book:

Who knew that American housewives were up in arms throughout the last century about rising food prices and misleading package information. Twarog traces the history of how these movements developed, their connections to unions and women’s auxiliaries, and how twentieth-century politics systematically destroyed them. Her book has much to teach us about what’s needed to preserve—and strengthen–today’s food movements.

I subscribe to GlobalMeatNews.com to keep me up on the international meat business. It has just published a collection of its articles—on pork.

Special Edition: Pork

Pork is the most eaten meat in world and maintaining the position is anything but easy. In this special newsletter, GlobalMeatNews explores the breakthroughs, scandals and market trends that continue to kept traders on their toes.

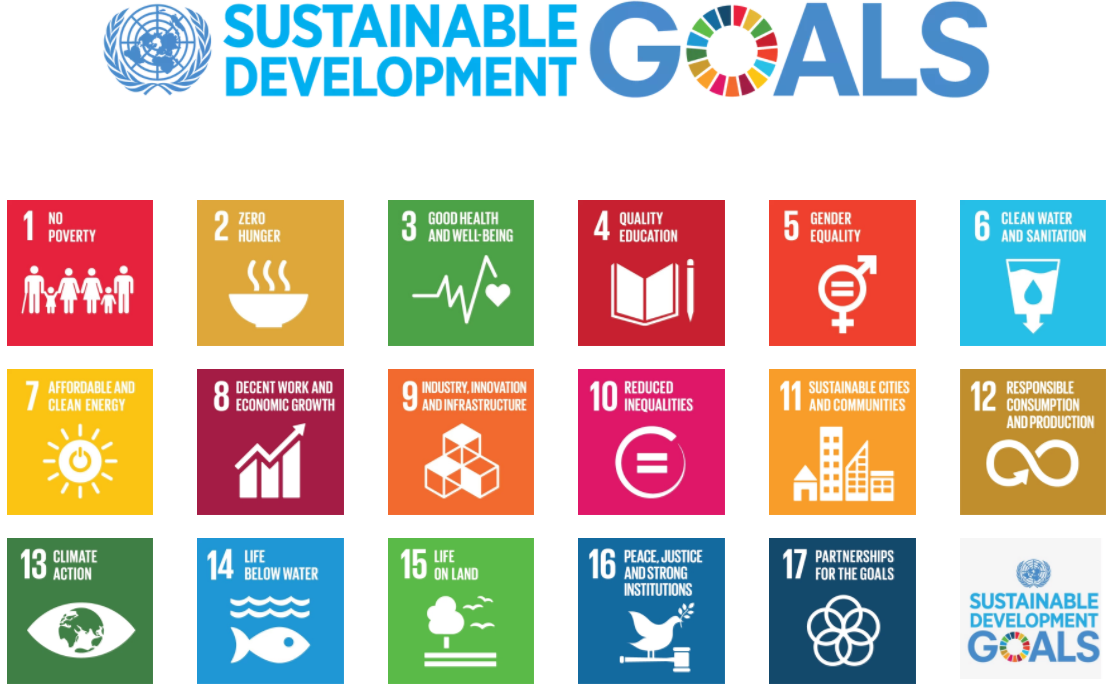

When I give talks these days, I usually wear a pin—the O in the United Nation’s Sustainable Development GOals (SDGs). These were authorized by the U.N. General Assembly in 2015 to be achieved by 2030.

Each goal has specific sub-goals. These are listed here in interactive format. Food comes up in several, but mainly in Goal 2 (End Hunger) and a bit in Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Here are the first three sub-goals for Goal 2:

The SDGs have sparked many organizations to take action. The U.N. makes taking small actions easy for individuals by producing “The Lazy Person’s Guide to Saving the World“—things you can do from your couch, your home, or outside your home.

Here’s the U.N. report on how progress toward the goals looked in 2016.

I wish chronic disease prevention was more prominent in these goals, which would make food more prominent, but this is a start and well worth knowing about.

Food regulation is no trivial matter. Every word on a food label has a Federal Register notice and Code of Federal Regulation section behind it.

Consequently, I was amused to learn that the FDA was not amused when it found the word “love” in the ingredient list of granola from Nashoba Brook Bakery. The FDA issued a warning letter with this presumably non-ironic statement:

Your Nashoba Granola label lists ingredient “Love”. Ingredients required to be declared on the label or labeling of food must be listed by their common or usual name [21 CFR 101.4(a)(1). “Love” is not a common or usual name of an ingredient, and is considered to be intervening material because it is not part of the common or usual name of the ingredient.

From its website, the bakery looks like it makes great stuff, but its owners must not be familiar with FDA’s byzantine regulatory requirements. The warning letter also chided the bakery for a long list of food safety violations, among them:

I hope the bakery gets its regulatory and food safety act together right away.

Personally, I like a little love in my granola.

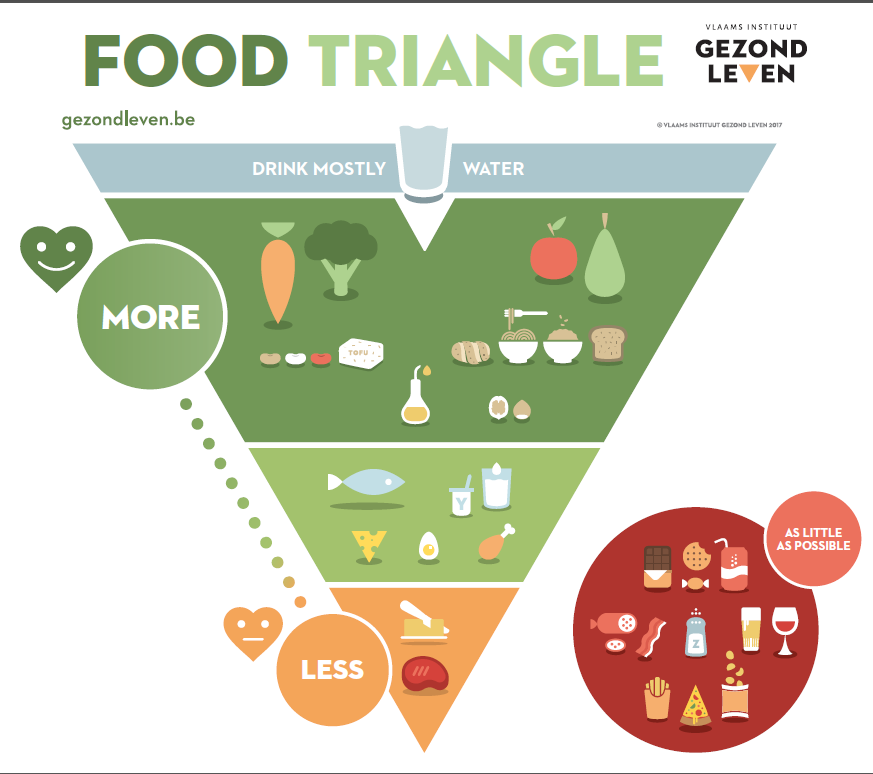

Belgium has produced a new food guide “pyramid,” upside down. Its advice:

Nothing new here, really, except for making the advice so graphically clear.

As Quartz puts it, “the new food pyramid in Belgium sticks meat next to candy and pizza.”

USDA: take note.

HLPE [High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition]. Nutrition and food systems. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome, 2017.

This report takes a food systems approach to recommendations for reducing the double burden of malnutrition—obesity in the presence of widespread hunger and its consequences.

This report aims to analyse how food systems influence diets and nutrition. It offers three significant additions to previous frameworks. First, it emphasizes the role of diets as a core link between food systems and their health and nutrition outcomes. Second, it highlights the central role of the food environment in facilitating healthy and sustainable consumer food choices. Third, it takes into account the impacts of agriculture and food systems on sustainability in its three dimensions (economic, social and environmental). 2. A food system gathers all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, and the outputs of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes. This report pays specific attention to nutrition and health outcomes of food systems. It identifies three constituent elements of food systems, as entry and exit points for nutrition: food supply chains; food environments; and consumer behaviour.

Protein occurs in most foods but is especially abundant in meat, poultry, fish, dairy, eggs, grains, beans, nuts, and seeds. Most of us get more than twice the amount we need on a daily basis.

But protein comes with a health aura. It sells.

Hence: the food industry’s great interest in developing protein ingredients for food products.

FoodNavigator-USA, ever on top of current food trends, summarizes recent developments.

Special Edition: Protein in focus

While Americans typically get enough, there is no sign that the protein trend is going away, with growing numbers of food and beverage brands seeking to add additional protein to their wares or highlight the protein that’s always been there. We take a closer look…