Leah Penniman. Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land Chelsea Green, 2018.

This is the second copy of this book sent by the publisher. The first was snapped up off my desk by a colleague who was desperate for this book, not even knowing it existed.

For good reason.

This book is way more than a how-to guide, although it does that part splendidly. It thoroughly integrates farming basics with necessary elements of supportive community, grounded in Penniman’s experience with Soul Fire Farm near Albany, New York.

Every section emphasizes the importance of community.

- On finding the right land: make sure it is geographically accessible to a community where you feel you can belong.

- On mission statements: train and empower aspiring Black, Latinx and indigenous growers; advance healing justice.

Every section emphasizes resources for Black farmers—scholarships, training programs, university programs, food hubs—and the contributions of traditional African and modern African-American farmers to what we know about how best to conduct sustainable agriculture.

The book is firmly grounded in history. I particularly appreciated the annotated timeline of the trauma inflicted on Black farmers induced by racism. This history begins with slavery, but continues through police brutality, convict leasing, sharecropping, Jim Crow laws, land theft, USDA discrimination, real estate redlining, and today’s mass incarceration and gaps in income, food access, and power.

Karen Washington wrote the Foreword:

We sat with pride as we went around the circle introducing ourselves, talking about our frustrations with not being represented at food and farming conferences. I sat in awe as this young Black woman [Penniman] engaged us in conversation about race and power…this masterpiece of indigenous sovereignty [Farming While Black] sheds light on the richness of Black culture permeating throughout agriculture.

From Penniman’s chapter on keeping seeds:

Just 60 years ago, seeds were largely stewarded by small farmers and public-sector plant breeders. Today, the proprietary seed market accounts for 82 percent of the seed supply globally, with Monsanto and DuPont owning the largest shares…Beyond simply preserving the genetic heritage of the seed it is also crucial to our survival that we preserve the stories of our seeds…our obligation is to keep the stories of the farmers who curated the seeds alive along with the plant itself. It matters to know that roselle is from Senegal and tht the Geechee red pea is an essential ingredient in the Gullah dish known as Hoppin’ John. In keeping the stories of our seeds alive, we keep the craft of our ancestors alive in our hearts.

Penniman offers suggestions for white readers who might want to help:

Adopting a listener’s framework is the first step for white people who want to form interracial alliances Rather than trying to “outreach” to people of color and convince them to join your initiative, find out about existing community work that is led by people directly impacted by racism and see how you can engage.

This is an important book for everyone who cares about farming and agrarian values, regardless of color.

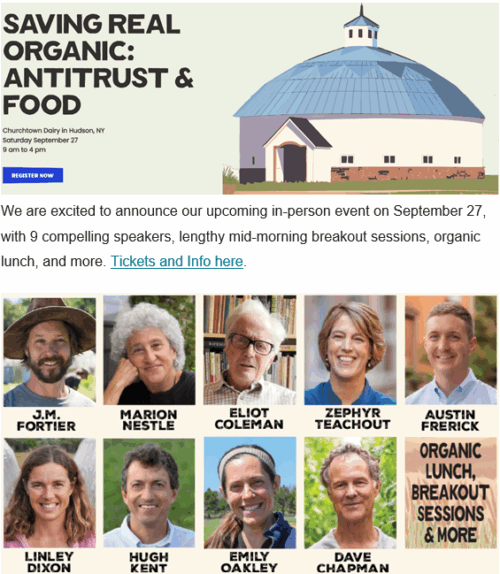

Tickets and information

Tickets and information