My monthly (first Sunday) Food Matters column in the San Francisco Chronicle appears today. This time, it’s about the fuss over front-of-package labels.

Q: I’m completely confused by all of the little check marks and squares on food packages telling me they are healthy. Do they mean anything?

A: The Food and Drug Administration feels your pain. It sponsored two studies by the Institute of Medicine to rationalize front-of-package nutrition ranking systems.

The institute released its second report last month; it advises the FDA to allow front-of-package labels to state nothing but calories and nutrients to avoid: saturated and trans fat, sodium and sugar (go to sfg.ly/sUptQR).

The institute’s proposal gives products one point for not containing too much of each of these nutrients. It suggests displaying the points like Energy Stars on home appliances with zero to three stars, depending on how well the product meets nutritional criteria.

This is a simple system, instantly understandable. I think it is courageous. The institute’s proposal benefits consumers. It does not help companies sell junk food.

Selling or educating?

No food company wants to display nutrients to avoid. For the food industry, the entire point of front-of-package labels is to market products as healthy or “better for you” no matter what they contain. Front-of-package labels are a tool for selling, not buying. They make highly processed foods look healthier.

Will companies accept a voluntary labeling scheme that makes foods seem worse? Doubtful.

Nutrition ranking symbols began appearing on food packages in the mid-1990s, when the American Heart Association got companies to pay for displaying its HeartCheck.

Food companies then established their own systems for identifying “better-for-you” products. PepsiCo, for example, developed its own nutritional standards and proclaimed hundreds of its snacks and drinks as “Smart Choices Made Easy.”

In an attempt to bring order to this chaos, food companies banded together to develop an industry-wide system. Unfortunately, their joint Smart Choices checkmark appeared first on Froot Loops and other sugary cereals. The ensuing ridicule and legal challenges forced the program to be withdrawn.

At that point, the FDA, backed by Congress and other federal agencies, asked the Institute of Medicine for help.

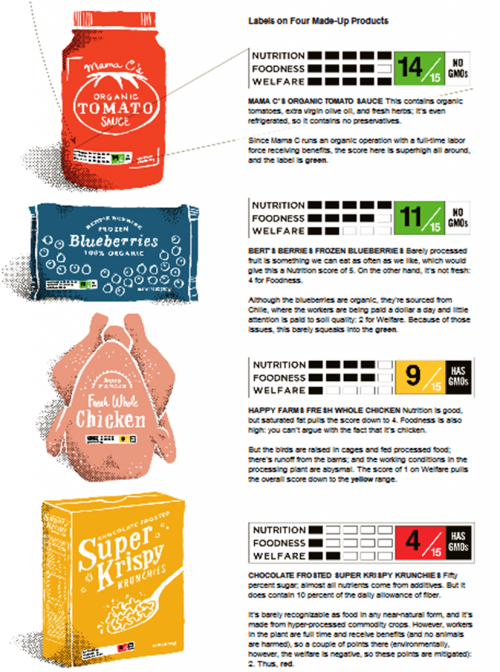

The institute released its first report last year. It revealed inconsistencies in the 20 existing ranking schemes from private agencies, food companies and supermarket chains. Toasted oat cereal, for example, earned two stars in one system, a score of 84 (on a scale of 100) in another, and a score of 37 in a third.

The report said labels should display only calories and to-be-avoided nutrients. Labels should not display “good-for-you” nutrients – protein, fiber, and certain vitamins and minerals – because these would only confuse consumers and encourage companies to unnecessarily add nutrients to products for marketing purposes.

Although the FDA was waiting for the second institute report before taking action, the food industry wasted no time. The Grocery Manufacturers Association and Food Marketing Institute introduced their own system.

Complicated approach

They got their members to agree to a more complicated system, “Nutrition Keys,” based on nutrients to avoid but also including up to two “good-for-you” nutrients.

Food companies immediately put Nutrition Keys’ symbols – well established to be difficult for consumers to understand – on package labels where you can see them today. Now called Facts Up Front, the symbols are backed by a $50 million “public education” campaign.

The reasons for the industry’s preemptive strike are obvious. The second Institute of Medicine report gives examples of products that qualify for stars – toasted oat cereal, oatmeal, orange juice, peanut butter and canned tomatoes, among them.

It also lists the kinds of products that would not qualify for stars, including animal crackers, breakfast bars, sweetened yogurt and chocolate milk.

So the industry argues that consumers “want simple and easy to use information and should be trusted to make decisions for themselves and their families … rather than have government tell them what they should and should not eat.”

But why, you ask, does any of this matter? I view front-of-package labels as a test of the FDA’s authority to regulate and set limits on any kind of food industry behavior. If the FDA cannot insist that food labels help the public choose healthier foods, it means the public has little recourse against any kind of corporate power.

Perhaps Facts Up Front will arouse the interest of attorneys general – just as the Smart Choices program did.

In the meantime, the industry’s pre-emption of FDA labeling initiatives is evidence that voluntary schemes don’t work. Labeling rules need to be mandatory.

Let’s hope the FDA takes the Institute of Medicine’s advice and starts rule-making right away.

Marion Nestle is the author of “Food Politics” and “What to Eat,” among other books, and is a professor in the nutrition, food studies and public health department at New York University. E-mail comments to food@sfchronicle.com.