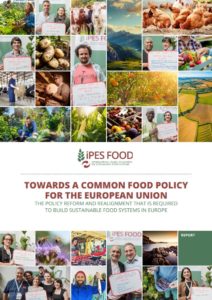

Weekend reading: A common food policy for the European Union

The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) has put together a thoughtful, detailed blueprint for creating a food policy that unites and integrates agriculture and health policies. This report is a model for what we should and can do in the United States.

What is this about?

A Common Food Policy is needed to put an end to conflicting objectives and costly inefficiencies. The policies affecting food systems in Europe – agriculture, trade, food safety, environment, development, research, education, fiscal and social policies, market regulation, competition, and many others – have developed in an ad hoc fashion over many years. As a result, objectives and policy tools have multiplied in confusing and inefficient ways. Gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions between policies are the rule, not the exception. Ambitious anti-obesity strategies coexist with agri-trade policies that make junk food cheap and abundant…

Its point?

A Common Food Policy would put an end to these costly inefficiencies by changing the way that policies are made: it would be designed to bring different policies into coherence, establish common objectives, and avoid trade-offs and hidden costs (or ‘externalities’). In other words, it would bring major benefits to people and the planet, and would ultimately pay for itself.

Documents

Why does this matter? Here, for example, is

Why does this matter? Here, for example, is