The crisis caused by Covid-19 reveals deep flaws in America’s health care system but also in its food system. The food system flaws are showing up first in the meat industry, reliant as it is on a low-wage, immigrant work force.

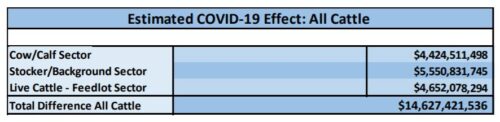

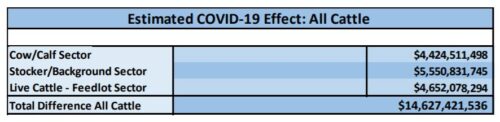

Cattlemen estimate virus-induced losses at more than $14 billion

Using existing market data and futures market data, the total actual and future impact is forecast to exceed $14.6 billion, broken out by sector in the table below.

U.S. Food Supply Chain Is Strained as Virus Spreads

The nation’s food supply chain is showing signs of strain, as increasing numbers of workers are falling ill with the coronavirus in meat processing plants, warehouses and grocery stores. The spread of the virus through the food and grocery industry is expected to cause disruptions in production and distribution of certain products like pork, industry executives, labor unions and analysts have warned in recent days. The issues follow nearly a month of stockpiling of food and other essentials by panicked shoppers that have tested supply networks as never before.

COVID-19 cases in Iowa packing plants a big part of 389 new cases, state’s largest single-day increase

Iowa had its largest single-day increase in COVID-19 cases Sunday, driven largely by new positive tests at meatpacking plants. State officials said 261 of the 389 new cases of COVID-19 reported Sunday were discovered as part of testing done at Iowa meat processing plants.

The food chain’s weakest link: slaughterhouses

Yet meat plants, honed over decades for maximum efficiency and profit, have become major “hot spots” for the coronavirus pandemic, with some reporting widespread illnesses among their workers. The health crisis has revealed how these plants are becoming the weakest link in the nation’s food supply chain, posing a serious challenge to meat production.

South Dakota Meat Plant Is Now Country’s Biggest Coronavirus Hot Spot

That all appeared to be in jeopardy this week, when the Smithfield plant became the nation’s largest single-source coronavirus hot spot. Its employees now make up about 44 percent of the diagnoses in South Dakota, and a team of researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has traveled there to assess how the outbreak spiraled out of control. Smithfield is the latest meat processing facility to close in the face of the coronavirus. The startling toll on the workers has drawn criticism from union leaders who say the facility’s owners waited too long to introduce safety measures, and instead encouraged employees to meet the demand for their products that has surged amid the pandemic.

Smithfield Foods Shuts U.S. Bacon, Ham Plants as Coronavirus Hits Meat Sector

Smithfield, owned by China’s WH Group Ltd, is shuttering a plant that processes bacon and sausage in Cudahy, Wisconsin, for two weeks, according to a statement. A facility in Martin City, Missouri, that processes spiral and smoked hams will also close. The Missouri plant, which employs more than 400 people, processes pork from the Smithfield slaughterhouse in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, that the company closed indefinitely. More than 200 employees became infected with the coronavirus at the South Dakota slaughterhouse, which produces 4% to 5% of the nation’s pork.

US Pork Farmers Panic as Virus Ruins Hopes for Great Year

Instead, restaurant closures due to the coronavirus have contributed to an estimated $5 billion in losses for the industry, and almost overnight millions of hogs stacking up on farms now have little value. Some farmers have resorted to killing piglets because plunging sales mean there is no room to hold additional animals in increasingly cramped conditions.

Poor Conditions at Meatpacking Plants Have Long Put Workers at Risk. The Pandemic Makes it Much Worse

The meat processing industry, where workers toil shoulder to shoulder in crowded, enclosed spaces, has been battered by the novel coronavirus in recent days. Multiple plants have closed after several thousand workers fell ill and tested positive for COVID-19 and a dozen have died—including three other workers at the JBS plant in Greeley, one at a Cargill plant in Fort Morgan, Colorado, four at a Tyson plant in Camilla, Georgia, two at another Tyson plant in Columbus Junction, Iowa, one at another JBS plant in Souderton, Pennsylvania, and one at the Smithfield pork factory in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. As of Wednesday, the Smithfield plant had become the country’s top COVID hotspot, with more than 640 cases linked to the plant.

Corporate focus on profits literally kills workers

The circumstances that engulfed the Sioux Falls pork plant are illustrative of many things: political denial, corporate greed, a Trumpist skepticism toward experts. But the Smithfield plant also epitomizes the stark differences between many wage earners and the professionals of the so-called information economy….The nation needs a stronger social safety net that includes, among other things, paid sick leave and parental leave, guaranteed health care and assistance for child care.

Food safety lawyer Bill Marler on unprotected workers and meat inspectors

- You cannot slaughter animals without workers to do the work, and you cannot sell meat without inspectors.

- We need to protect both workers and inspectors or we will see more plants shutter and our grocery stores empty.

- Forcing workers and inspectors to work unprotected is not the answer

Resource

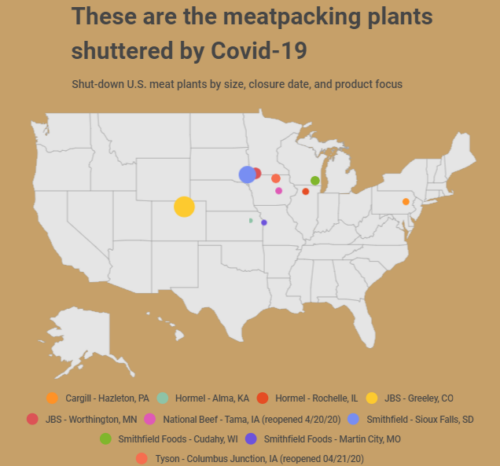

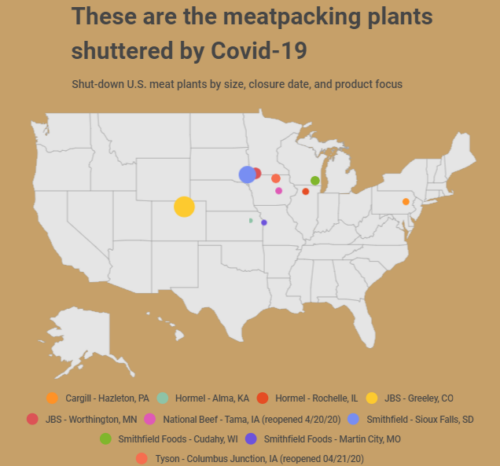

The Counter has a nifty interactive map of closed meatpacking plants as part of a useful Q and A (go to the link to use the interactive parts).