Stanford University issued a press release to announce the results of a study comparing physiological effects of eating plant-based meat alternatives (Beyond Meat) to eating foods of animal origin.

A diet that includes an average of two servings of plant-based meat alternatives lowers some cardiovascular risk factors compared with a diet that instead includes the same amount of animal meat, Stanford Medicine scientists found.

The study: A randomized crossover trial on the effect of plant-based compared with animal-based meat on trimethylamine-N-oxide and cardiovascular disease risk factors in generally healthy adults: Study With Appetizing Plantfood—Meat Eating Alternative Trial (SWAP-MEAT). Crimarco A, et al. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, August 11, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa203

Overall conclusion: “This study found several beneficial effects and no adverse effects from the consumption of plant-based meats.”

The sponsor: “Supported by a research gift from Beyond Meat Inc. (to CDG)…Funding for this study was provided by Beyond Meat. In an effort to reduce any influences on the outcomes of this study, a statistical analysis plan was submitted to ct.gov. The main analysis was conducted by a third-party individual who had no involvement with the study design or collection of data, and was blinded to all study participants.

Comment

Ordinarily, I would simply present this study as a classic example of how industry-funded studies predictably produce results that favor the commercial interests of their sponsors, a topic to which I devoted my book, Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat.

But CDG is Christopher Gardner, the study’s lead scientist, whose impressive track record of managing complicated clinical trials of diet and health I greatly admire.

Gardner describes himself as a vegan (meaning that he eats no animal products).

Knowing of my concerns about industry-funded research, he wrote me some months ago to say that this study was in the works and to point out that he has done at least six industry-funded studies with null findings (he sent me a PowerPoint slide deck to prove it). In his correspondence, he said:

- “I believe this is the FIRST industry funded study I’ve run that had a significant positive health finding.”

- “Beyond Meat was not involved in design or analysis, and to this day still doesn’t know the study outcome.”

- “I’m preparing myself for being called out as a vegan industry shill….hoping I’ve established a reputation for objectivity to withstand this ?”

- “PS – Hope you enjoy the study acronym (Study With Alternative Plantfood – Meat Eating Alternative Trial: SWAP-MEAT)” [Indeed I do].

OK. So let’s take this study on its merits.

Gardner asked healthy non-vegetarian adults (36) to consume 2 servings a day of either Beyond Meat or regular meat (what the study calls Animal Meat). The Beyond Meat and Animal Meat were provided to participants. The rest of their diets was on their own.

For 8 weeks, they ate Beyond Meat or Animal Meat. For the next 8 weeks, they switched over to the other kind.

Results: Participants consuming Beyond Meat displayed lower levels of

- LDL-cholesterol (the bad kind)

- Body weight (by 1 or 2 pounds)

- TMAO (Trimethylamine N-oxide)—but only for those who consumed Animal Meat first and Beyond Meat second (not the other way around)

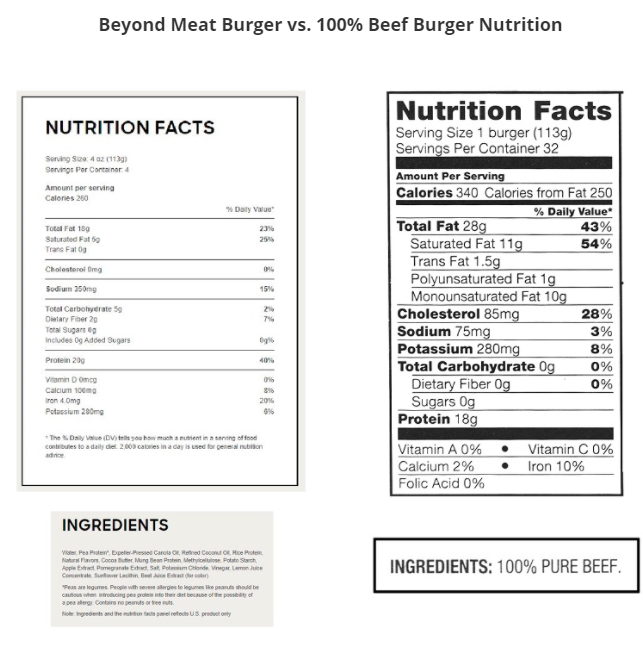

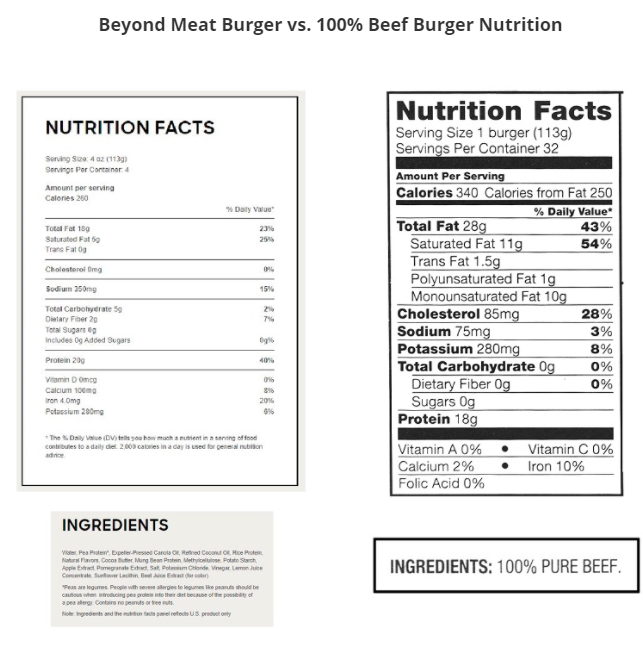

Beyond Meat may be plant-based, but it is ultraprocessed. FoodNavigator produced a nice comparison.

Beyond Meat would dearly love to demonstrate that its ultraprocessed composition is immaterial to its health benefits. Hence: this study.

Beyond Meat is already using it for marketing purposes: “New study finds health benefits of plant-based meats.”

As I see it, there are two issues here: (a) what else the participants were eating and (b) the significance of the TMAO measurements.

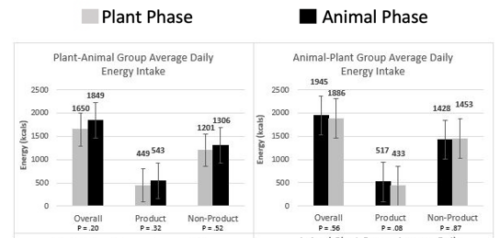

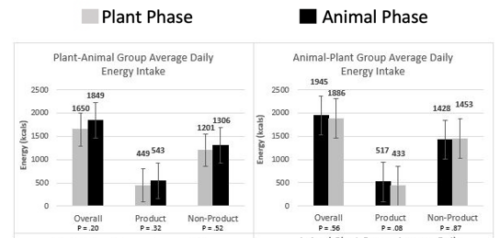

(a) The diet: This was not a controlled dietary intake trial conducted in a closed metabolic ward. Participants were free to eat whatever they liked and how much they liked. They lost a little weight during the Beyond Meat phase, which means they must have been eating fewer calories during that phase, as they reported (this graph is in the Supplementary material).

Reported daily calories were under 2000, which means that lots of calories must not have been reported. So it’s hard to know what the weight loss is actually due to.

(b) TMAO: You make TMAO after you eat foods containing choline, a compound common in animal-based foods: meat, poultry, fish, and eggs. A 2019 editorial review in JAMA discusses the association of TMAO with heart disease risk.

Now, researchers are homing in on another possible culprit: a dietary metabolite linked to red meat called trimethylamine N-oxide, or TMAO. Three recent meta-analyses confirmed that high blood levels of TMAO are associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. One of the studies, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association in 2017, found a more than 60% heightened risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and death from all causes in people with elevated TMAO. Other research has associated higher TMAO levels with heart failure and chronic kidney disease.

On the other hand, an analysis by Dr. Bret Scher raises questions about whether TMAO has any real meaning for health (and I thank Stephen Zwick for sending this to me).

In my opinion, this is an example of a well-run study that, in the end, lends very little to our knowledge of human health….The main outcome from this intervention had to do with TMAO. Why is this problematic? Well, it has to do with the fact that small, short-term trials are unable to measure meaningful endpoints, such as who lives, dies, or who gets heart disease. So, instead, the authors have to choose the surrogate outcome markers that they believe relate to human health.

Dr. Scher believes that “There is no convincing evidence that these results impact someone’s health.” As Scher has discussed previously, he sees no cause-and-effect relationship between TMAO levels and health. You can read his arguments here:

The bottom line? This study suggests that two servings a day of Beyond Meat is unlikely to be harmful. Whether substituting Beyond Meat for real meat is truly useful for health in the absence of other dietary changes remains to be confirmed, hopefully by independently funded research.

I did a blurb for this book:

I did a blurb for this book: