The American Heart Association’s new and groundbreaking dietary guidelines

The American Heart Association (AHA) has just issued its latest set of dietary guidelines aimed at preventing the leading cause of death in the United States: 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.

Because AHA guidelines apply not only to coronary heart disease but also to all other chronic disease conditions—and sustainability issues—influenced by dietary practices, they deserve special attention.

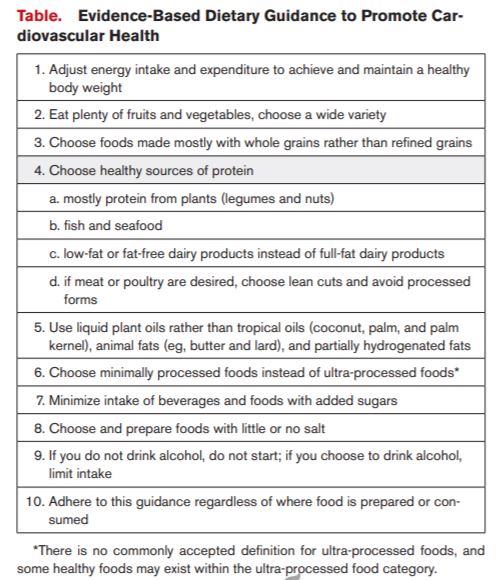

Most of these repeat and reinforce the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

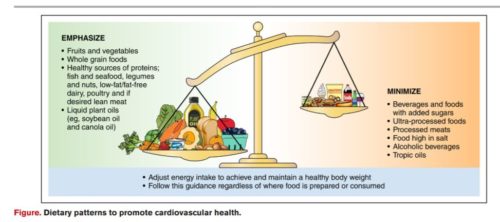

The two big differences in the recommendations:

- Clarifying protein recommendations: these include all sources but emphasize plant sources (#4)

- Including a new one: minimize ultra-processed foods (#6)

These recommendations are way ahead of the US Dietary Guidelines in recognizing how much ultra-processed foods contribute to poor health, and how important it is to minimize their intake.

Also unlike the US guidelines, these are unambiguous and easily summarized.

The statement is worth reading for its emphasis on two other points.

- This dietary pattern addresses problems caused by other chronic conditions and also has a low environmental impact.

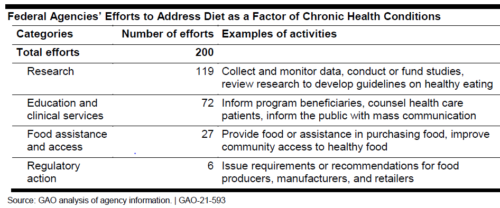

- Following this dietary pattern requires much more than personal responsibility for food choices. It requires societal changes as well.

The press release summarizes the problems in society that make following healthy diets so difficult, if not impossible:

- Widespread dietary misinformation from the Internet;

- A lack of nutrition education in grade schools and medical schools;

- Food and nutrition insecurity – According to references cited in the statement, an estimated 37 million Americans had limited or unstable access to safe and nutritious foods in 2020;

- Structural racism and neighborhood segregation, whereby many communities with a higher proportion of racial and ethnic diversity have few grocery stores but many fast-food outlets; and

- Targeted marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to people from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds through tailored advertising efforts and sponsorship of events and organizations in those communities.

As the statement concludes: “Creating an environment that facilitates, rather than impedes, adherence to heart-healthy dietary patterns among all individuals is a public health imperative.”

Amen to that.

Comment: From my perspective, this statement thoroughly supersedes the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which—because they say nothing about ultra-processed foods , differential protein sources, sustainability, or doing anything to counter societal determinants of poor diets—were out of date the instant they appeared.

Some of the details of the AHA statement will be debated but its overall approach should not be.

The committee that put these guidelines together deserves much praise for basing its advice on today’s research and most pressing societal needs.

Additional AHA Resources:

- Spanish news release

- Available multimedia is on right column of release link: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/new-look-at-nutrition-research-identifies-10-features-of-a-heart-healthy-eating-pattern?preview=288ef57763869cab946e725d341dbb63

- After Nov. 2, 2021, view the manuscript online.

- What kind of diet helps heart health?

- Eating walnuts daily lowered bad cholesterol and may reduce cardiovascular disease risk

- Eating more plant foods may lower heart disease risk in young adults, older women

- Sugar 101

- Follow AHA/ASA news on Twitter @HeartNews

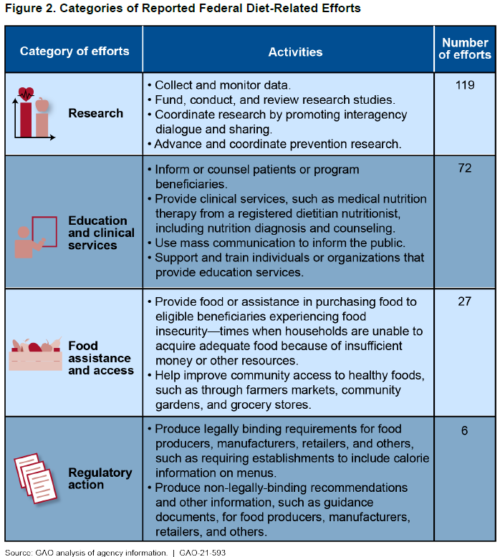

Most of these are focused on research.

Most of these are focused on research.