How’s this for an idea: April Food Day

If you, like me, are not in the mood for jokes that won’t seem funny today, here’s an idea for an alternative.

If you, like me, are not in the mood for jokes that won’t seem funny today, here’s an idea for an alternative.

The Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) has produced a report on soda taxes in the region.

What’s happening with soda taxes in Latin America is impressive.

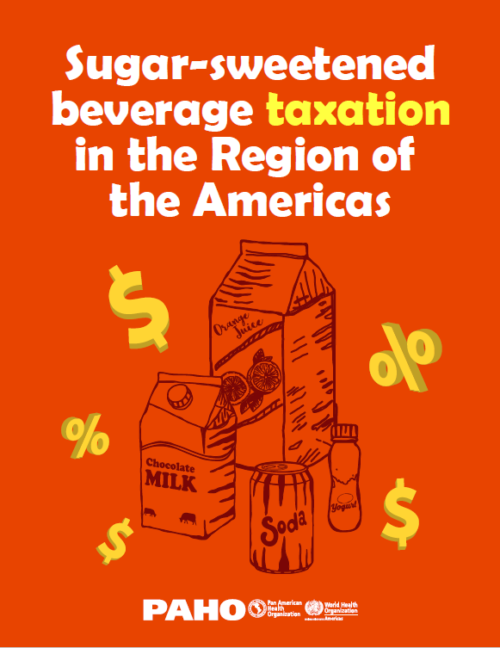

Soda taxes, no matter where they are, seem to be doing what they are supposed to:

Latin America is a model for Dietary Guidelines (Brazil) and front-of-package warning labels (Chile).

Wish we could do these things.

A dietitian colleague forwarded this message from Today’s Dietitian.

Honey may be made by bees, but it is mainly glucose and fructose just like any other sugars.

A few “food-for-thought” questions:

Carey Gillam. The Monsanto Papers: Deadly Secrets, Corporate Corruption, and One Man’s Search for Justice. Island Press, 2021.

Gillam, the author of Whitewash, a book for which I did a blurb (and who works for U.S. Right to Know) has surpassed herself and written what I can only descxribe as a blockbuster, right up there with page-turning thrillers by John Grisham.

I could not put this book down, and cannot recommend it highly enough.

It is the story of a school groundskeeper, Lee Johnson, who one working day set out to spray Roundup to kill weeds, but had an accident and got soaked with it. He later developed a form of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) that has been associated with exposure to this weed killer.

Once Roundup’s main ingredient, glyphosate, was judged “probably carcinogenic” by the International Agency for Cancer Research, lawyers got involved and Johnson was chosen for the first case to try.

Gillam documents what the maker of Roundup, Monsanto, did to hide evidence of this chemical’s carcinogenicity, how it funded its own studies, ghost-wrote others, and established cozy relationships with EPA officials (hence “corporate corruption”).

She also tells the legal story. Even though I knew the outcome before I picked up the book—I track such things—I found the details about the preparation of the case and actual trial riveting.

This is because this book is fabulously written—as I said, I couldn’t stop reading it—but also because she makes the characters in this drama come alive. It reads like a novel.

It’s also an important book. Monsanto is infamous for bad corporate behavior (“Monsatan”) but what’s documented here is truly shocking. I shouldn’t have been shocked because I had written about Monsanto in my 2003 book about food biotechnology, Safe Food: The Politics of Food Safety. I had written my own account of its bad behavior.

Gillam brings the story up to the point where the German pharmaceutical firm, Bayer, bought Monsanto for $63 billion, something I hope this company has regretted ever since.

Spoiler alert: The most recent development in this case happened just last week.

I’m always interested in how the food industry tries to sell products to specific groups. Here’s one of FoodNavigator’s Special Editions (collections of articles) on products the food industry is designing and trying to sell for older adults.

Special Edition: Healthy ageing: Food for an older population

Europe is ageing. By 2050 the population of over 65s is expected to reach almost 150m in the region. Gains are expected for products that cater to this older demographic by boosting immunity, as well as bone, joint, muscle, cognitive, heart, skin, eye and digestive health. FoodNavigator looks at some of the innovation strategies food makers are developing to meet the needs of older people.

I’ve just had a book review published in the American Journal of Public Health: “Public health nutrition deserves more attention.”

It’s for a textbook on public health nutrition but doing it gave me the opportunity to say some things I want public health professionals to know. I started the review like this:

Public Health Nutrition deserves more attention

Food and nutrition deserve much more attention from public health professionals. On the grounds of prevalence alone, diet-related conditions affect enormous numbers of people. Everybody eats. Everybody is at risk of eating too little for health or survival, or too much to the point of weight gain and increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). By the latest count, nearly 700 million people in the world do not get enough to eat on a daily basis, a number that has increased by tens of millions over the past five years and will surely increase by many millions more as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic.[i] At the same time, about two billion adults are overweight or obese, and few countries are prepared to deal with the resulting onslaught of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.[ii] Beyond that, food production, distribution, consumption, and disposal—collectively food systems—are responsible for a quarter or more of greenhouse gas emissions; climate change affects the health of everyone on the planet.[iii]

The same social, behavioral, economic, and structural determinants that affect health also affect nutritional health, and it is no accident that food choices are flash points for arguments about culture, identity, social class, inequity, and power, as well as about the role of government, private enterprise, and civil society in food systems. From a public health standpoint, everyone–regardless of income, class, race, gender, or age—should have the power to choose diets that meet nutritional needs, promote health and longevity, protect the environment, and are affordable, culturally appropriate, and delicious.

Nutrition in 2021

For people in high-income countries, dietary prescriptions for health and sustainability advise eating less meat but more foods from plant sources.[iv] Optimal diets should minimize consumption of ultra-processed foods, those that are industrially produced, bear little resemblance to the basic foods from which they were derived, cannot be prepared in home kitchens, and are now compellingly associated with NCD risk and mortality.[v] We now know that ultra-processed foods encourage people to unwittingly take in more calories and gain weight.[vi]

Agenda for 2021

Today, a book for researchers and practitioners of public health nutrition needs to emphasize coordinated—triple-duty—recommendations and interventions to deal with hunger and food insecurity, obesity and its consequences, and the effects of food production and dietary choices on the environment. Such approaches, as described by a Lancet Commission early in 2019,4 should encourage populations of high-income countries to eat less meat but more vegetables, those in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to consume a greater variety of foods, and everyone, everywhere to reduce intake of ultra-processed foods. As that Commission argued, public health nutritionists must recognize that attempts to improve diets, nutritional status, nutritional inequities, and food systems face daunting barriers from governments captured by corporations, civil society too weak to demand more democratic institutions, and food companies granted far too much power to prioritize profits at the expense of public health. Nutritionists need knowledge and the tools to resist food company marketing and lobbying, to advocate for regulatory controls of those practices, and to promote civil society actions to demand healthier and more sustainable food systems.[vii]

I then go on to talk about the book itself, which alas, did not have much to say about this agenda.

References to the first part of this review

[i] The World Bank. Brief: Food Security and COVID-19. December 14, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19#:~:text=In%20November%202020%2C%20the%20U.N.,insecure%20people%20in%20the%20world. Accessed January 2, 2021.

[ii] WHO. Obesity and overweight: Key facts. Geneva: WHO. April 1, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed January 2, 2021.

[iii] International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems. COVID-19 and the crisis in food systems: symptoms, causes, and potential solutions. IPES-Food, April 2020. www.ipesfood.org/pages/covid19. Accessed January 2, 2021.

[iv] Swinburn BA, Kraak V, Allender S, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2019;393:791–846.

[v] Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(5):936–941.

[vi] Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30, 67–77.

[vii] Jayaraman S, De Master K, eds. Bite Back: People Taking On Corporate Food and Winning. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2020.

I cannot believe that we are still talking about whether vitamin C prevents colds. No such luck.

What triggered this is a recent and quite detailed critique of a 2018 meta-analysis of studies of this question: “Extra Dose of Vitamin C Based on a Daily Supplementation Shortens the Common Cold: A Meta-Analysis of 9 Randomized Controlled Trials.”

Its conclusion: “The combination of supplemental and therapeutic doses of vitamin C is capable of relieving chest pain, fever, and chills, as well as shortening the time of confinement indoors and mean duration.”

You can read the detailed critique of this study for yourself, but I thought this was settled years ago by one of my all-time favorite nutrition studies: Karlowski TR, Chalmers TC, Frenkel LD, Kapikian AZ, Lewis TL, Lynch JM. Ascorbic acid for the common cold. A prophylactic and therapeutic trial. JAMA 1975; 231: 1038–1042.

This fabulous study was done at NIH using NIH employees. As the abstract puts it,

Three hundred eleven employees of the National Institutes of Health volunteered to take 1 gm of ascorbic acid or lactose placebo in capsules three times a day for nine months. At the onset of a cold, the volunteers were given an additional 3 gm daily of either a placebo or ascorbic acid.

The initial analysis of the data showed a highly significant effect of vitamin C in preventing colds or reducing symptoms. But the trial had one major flaw: it had an usually big dropout rate.

One hundred ninety volunteers completed the study. Dropouts were defined as those who missed at least one month of drug ingestion. They represented 44% of the placebo group and 34% of those taking ascorbic acid.

These were good investigators. They asked the dropouts why they had dropped out. The reason: the study subjects knew (well, they thought they knew) whether they were taking vitamin C or the placebo.

The investigators reanalyzed the data according to what the study subjects thought they were taking. Those who thought they were taking vitamin C had fewer colds and reduced symptoms—regardless of whether they were taking vitamin C or the placebo. And those who thought they were taking the placebo had more colds and worse symptoms regardless of whether they really were taking the placebo or were actually taking vitamin C.

The authors’ cautious conclusion:

Analysis of these data showed that ascorbic acid had at best only a minor influence on the duration and severity of colds, and that the effects demonstrated might be explained equally well by a break in the double blind.

My conclusion: Vitamin C is one terrific placebo.

Nothing wrong with that, but that’s why I can’t believe investigators are still arguing about it.