The first lawsuit against ultra-processed foods

The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee may not think there is much to ultra-processed foods (UPF), but companies making them have just been served with a lawuit.

I learned about this from a tweet (x) from Carlos Monteiro, the Brazilian public health professor who coined the UPF term.

CMonteiro_USP (@Carlos A. Monteiro) posted: A first-of-its-kind lawsuit against 11 UPF industries alleging they engineer their UPF products to be addictive with details on the actions taken to target children including internal memos, meetings & the research conducted to create addictive substances.

The lawsuit, filed by several law firms, is aimed at Big Food: Kraft, Mondelez, Post, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, General Mills, Nestle, Kellanova, WK Kellogg, Mars, and Conagra.

The suit charges that these firms, through their deliberate marketing, are making people sick.

Due to Defendants’ conduct, Plaintiff regularly, frequently, and chronically ingested their UPF, which caused him to contract Type 2 Diabetes and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Plaintiff is now suffering from these devastating diseases, and will continue to suffer for the rest of his life.

The suit makes interesting reading.

Some examples:

- Big Tobacco companies intentionally designed UPF to hack the physiological structures of our brains. These formulation strategies were quickly adopted throughout the UPF industry, with the goal of driving consumption, and defendants’ profits, at all costs.

- The same MRI machines used by scientific researchers to study potential cures for addiction are used by UPF companies to engineer their products to be ever more addictive.

- Big Tobacco repurposed marketing strategies designed to sell cigarettes to children and minorities, and aggressively marketed UPF to these groups.

- The UPF industry now spends about $2 billion each year marketing UPF to children.

- UPF increase the risks of disease because they are ultra-processed, not because of how many grams of certain nutrients they contain or how much weight gain they cause. Therefore, even attempts to eat healthfully are undermined by the ultra-processed nature of UPF. One cannot evade the risks caused by UPF simply by selecting UPF with lower calories, fat, salt, sugar, carbohydrates, or other nutrients.

- The UPF industry is well aware of the harms they are causing and has known it for decades. But they continue to inflict massive harm on society in a reckless pursuit of profits.

Can’t wait to see what happens with this one. Stay tuned.

Resources

Consumer Federation of America: “Ultra-processed Foods: Why They Matter and What to Do About It.”

With government officials reluctant to issue advice on ultra-processed foods (UPFs), Consumer Federation of America aims to raise awareness about research on UPFs, explain the leading theories of how they harm health, and build support for public policies to reduce harms from UPFs in our diet.

The report pushes back on arguments that researchers have not consistently defined UPFs, or that the categorization lacks scientific rigor. In fact, researchers have operationalized the “Nova classification” system behind UPFs in a largely consistent manner, defining foods based on whether they contain ingredients that are “industrial formulations” or “rarely used in home kitchens,” with little serious disagreement about which ingredients should be considered “ultra processed.” Consumers can take CFA’s online quiz to test their knowledge of which ingredients are markers of “ultra processing.”

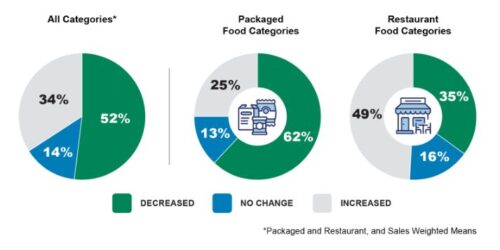

New research: Trends in Adults’ Intake of Un-processed/Minimally Processed, and Ultra-processed foods at Home and Away from Home in the United States from 2003–2018. J Nutr 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2024.10.048. The data show that 50% or more of calories are consumed from UPF at home, away from home, and by pretty much everyone.

New research: Hagerman CJ, Hong AE, Jennings E, Butryn ML. A Pilot Study of a Novel Dietary Intervention Targeting Ultra-Processed Food Intake. Obes Sci Pract. 2024 Dec 8;10(6):e70029. doi: 10.1002/osp4.70029. Behavioral interventions to reduce UPF intake cut calories by about 600 calories per day.

My post summarizing the three studies demonstrating that diets high in UPF induce intake of an excess of 500, 800, and 1000 calories per day.