GAO: USDA discriminates against minority, new, and military farmers

I love Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports. Some member of Congress requests them and GAO resaearchers then get to work.

I particularly like the way GAO understates what its reports are about.

Try this, for example: Oversight of Future Supplemental Assistance to Farmers Could Be Improved

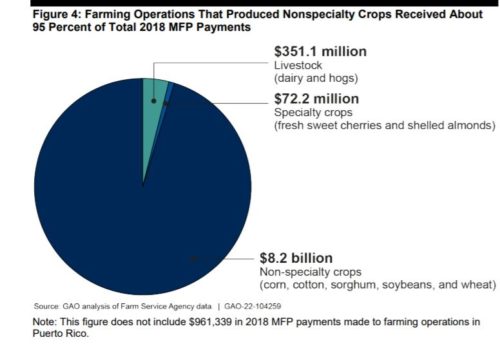

This program gave $23 billion to farmers during the pandemic.

Of this, 95% went to “nonspecialty crops” (translation: feed for animals and fuel for cars, aka Big Ag).

And hardly any of the money went to minority, new, or military farmers.

Leah Douglas, now working for Reuters, did the math.

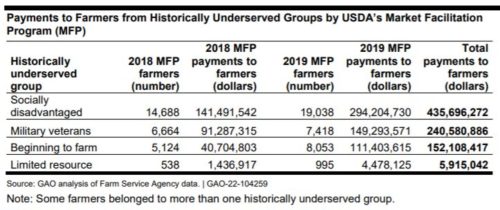

- Collectively, socially disadvantaged, military, and beginning farmers got a combined $818 million across the two years,—3.6%

- Socially disadvantaged farmers got $435.7 million—1.9% (they comprise 6.7% of farmers)

- Beginning farmers got $152.1 million—0.7% (they comprise 27% of farmers).

- Military veterans got $240.5 million—1% (they comprise 11% of farmers).

Comment: The USDA has a long history of discrimination against these groups. It needs to make up for that.