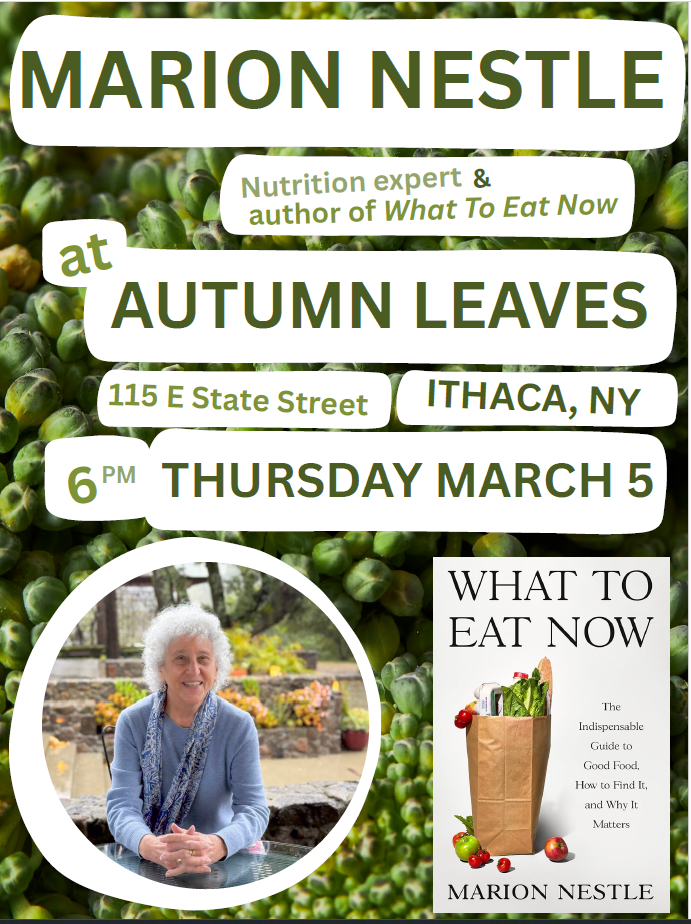

I was in Washington DC last week when the FDA announced that it was taking significant steps to address antibiotic resistance, a problem caused by overuse in raising animals for food.

The FDA called on makers of animal antibiotics to:

- Voluntarily stop labeling medical important antibiotics as usable for promoting animal growth or feed efficiency (in essence, banning antibiotics from these uses).

- Voluntarily notify the FDA of their intent to sign on to these strategies within the next three months.

- Voluntarily put the new guidance into effect within 3 years.

- Agree to a proposed rule to require a veterinarian’s prescription to use antibiotics that are presently sold over the counter (the proposal is open for public comment for 90 days at www.regulations.gov. Docket FDA-2010-N-0155).

Voluntary is, of course, a red flag and the Washington Post quoted critics saying that the new guidance falls far short of what really is needed—a flat-out ban on use of antibiotics as growth promoters.

- Consumers Union is concerned about the long delay caused by the 3-year window.

- CSPI is worried about all the loopholes.

- NRDC thinks the FDA is pretending to do more than it’s really doing and “kicks the can significantly down the road.”

- Mother Jones points out that the meat industry can still “claim it’s using antibiotics ‘preventively,’ continuing to reap the benefits of growth promotion and continue to generate resistant bacteria.”

- Civil Eats reminds us that the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production (on which I served) recommended a ban on nontherapeutic use of all antibiotics.

Yes, the loopholes are real, but I view the FDA’s guidance as a major big deal. The agency is explicitly taking on the antibiotic problem. It is sending a clear signal to industrial farm animal producers that sooner or later they will have to:

- Stop using antibiotics as growth promoters.

- Stop using antibiotics indiscriminately, even for disease treatment.

I think the FDA is dead serious about the antibiotic problem. If the FDA seems to be doing this in some convoluted fashion, I’m guessing it’s because it has to. The FDA must not have been able to find any other politically viable way to get at the antibiotics problem.

I see this as a first step on the road to banning antibiotics for any use in animals other than the occasional treatment of specific illnesses.

As the New York Times puts it,

This is the agency’s first serious attempt in decades to curb what experts have long regarded as the systematic overuse of antibiotics in healthy farm animals, with the drugs typically added directly into their feed and water. The waning effectiveness of antibiotics — wonder drugs of the 20th century — has become a looming threat to public health. At least two million Americans fall sick every year and about 23,000 die from antibiotic-resistant infections.

Still not convinced antibiotics are worth banning for promoting growth?

The best explanation is the Washington Post’s handy guide to the antibiotic-perplexed. Here, for example, is its timeline of development of microbial resistance to antibiotics. The bottom line: the more widespread the use of antibiotics, the greater the onset and prevalence of resistance. And it takes practically no time for bacteria to develop resistance to antibiotic drugs.

Resources from FDA