Food Politics Canada: A Roundup

I’ve been hearing a lot about Canadian food politics lately—lots is going on up there, apparently.

I. Health Canada is working on guiding principles for healthy diets—dietary guidelines–and is conducting an online consultation for feedback. The proposed principles:

- A variety of nutritious foods and beverages are the foundation for healthy eating.

- Processed or prepared foods and beverages high in sodium, sugars, or saturated fat undermine healthy eating.

- Guidelines should consider determinants of health, cultural diversity, and the food environment.

I hope these get a lot of support.

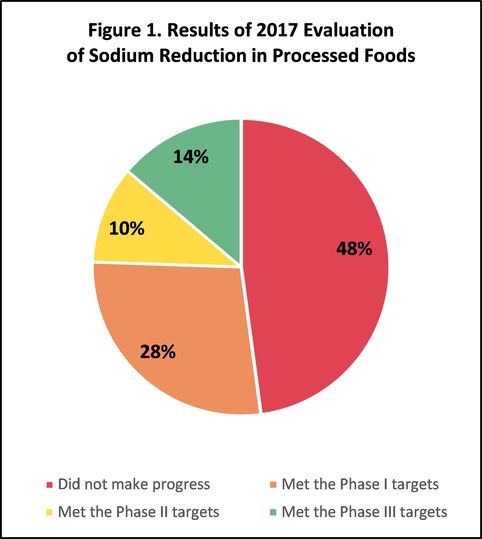

II. Sodium reduction in processed foods. Health Canada has just announced the results of its study of how well voluntary sodium reduction is working. The evaluation results are disappointing, and much more needs to be done. Mandatory reduction, anyone?

III. Front-of-package labels. Dr. Yoni Freedhoff writes that the Canadian food industry does not like what Health Canada is proposing to do about front-of-package labels.

Health organizations want something like this:

The food industry, no surprise, prefers this:

For more about this dispute, see this article from The Globe & Mail.

IV. Farm-to-school grants. Yoni Freedhoff also writes that Farm-to-Cafeteria Canada is offering $10,000 grants to Canadian Schools to set up such programs. Details here.