The USDA’s Economic Research Service was damaged serriously when the Trump Administration moved its offices out of Washington DC to Kansas, and it is taking some time to recover.

It’s still publishing what it calls Charts of Note.

These are on all kinds of topics dealing with farm production and food consumption. Here are a couple of examples I found particularly interesting.

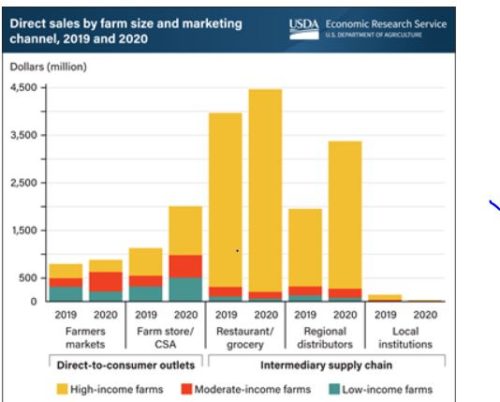

Here’s the first:

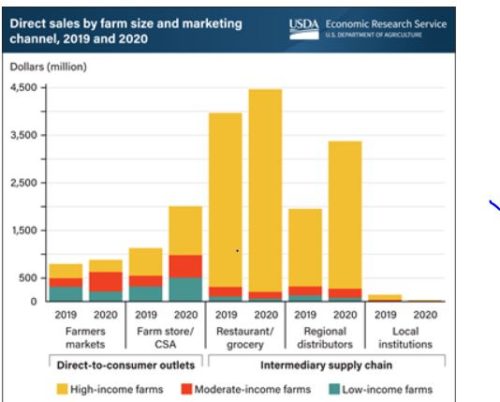

This one shows that small and medium size farms make money selling direct to consumers at farmers’ markets and via Community Supported Agriculture, but the largest farms benefit most from these opportunities. Restaurants and grocery stores don’t source much from smaller farms and neither do regional distributors.

The challenge for small and medium size farms is to find more and better distribution channels.\

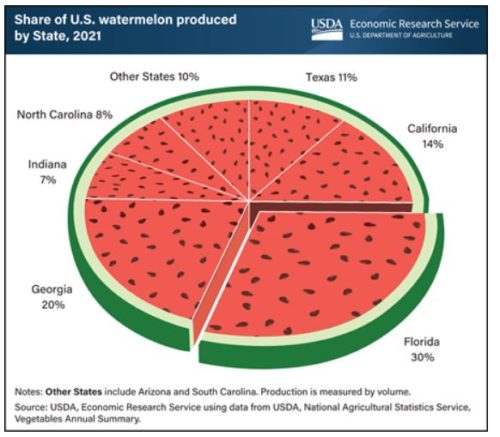

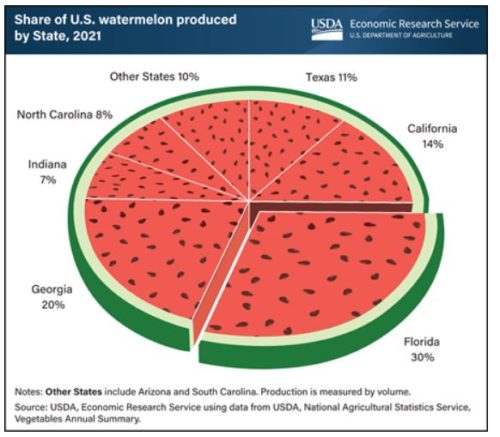

And here’s the second:

I picked this one because I like the design and because this watermelon has seeds. You can hardly buy a watermelon with seeds anymore.

I’ve been convinced that seedless watermelons don’t taste as good as the ones with seeds. This year, I bought some seeds from old-fashioned watermelon and planted them in my place in Ithaca, New York. They are now ripe, and edible. But alas: I don’t think they taste any better than the ones without seeds.

Next year, we plant seedless.

One big question: how do you get create seeds for seedless watermelons? This, I had to look up.

Seedless melons are referred to as triploid melons while ordinary seeded watermelons are called diploid melons, meaning, that a typical watermelon has 22 chromosomes (diploid) while a seedless watermelon has 33 chromosomes (triploid). To produce a seedless watermelon, a chemical process is used to double the number of chromosomes. So, 22 chromosomes are doubled to 44, called a tetraploid. Then, the pollen from a diploid is placed on the female flower of the plant with 44 chromosomes. The resulting seed has 33 chromosomes, a triploid or seedless watermelon. The seedless watermelon is sterile. The plant will bear fruit with translucent, nonviable seeds or “eggs.”

Aren’t you glad I asked?

************

Coming soon! My memoir coming out in October.

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.