The USDA announced last week the arrival of the Scientific Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC).

The DGAC deserves much praise for getting this job done on time under what I consider to be difficult constraints (large committee size, large areas of research to review, requirement that all recommendations be “evidence-based” which sounds good, but is unreasonable given the inability to conduct long-term controlled clinical studies).

The report is now open for public comment (see information at bottom of post).

The process to develop the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030 is under way. Get involved by providing written and oral comments to the Departments on the Scientific Report of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (Scientific Report). You may also sign up to receive email updates on news related to the development of the next edition of the Dietary Guidelines…For more information, visit the Public Comments to the Departments page.

A reminder about the process: The DGAC report is advisory. Since 2005, the agencies appoint an entirely separate internal governmental committee to write the actual guidelines. This, of course, makes the process far more political and subject to lobbying (file comments!).

The recent election will install new leaders of USDA and HHS. If they follow the same process, they will appoint and instruct the new committee. Or, they can change the process entirely.

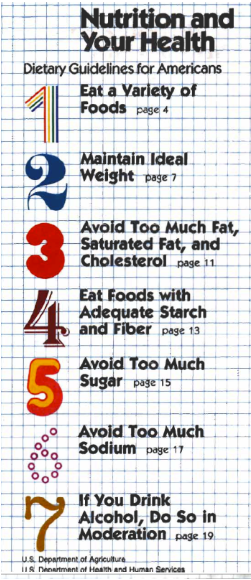

Another reminder: When I was on the DGAC in 1995, our committee chose the research questions, did the research, wrote the scientific report, and wrote the actual guidelines. Those were the days.

Comments on the DGAC report

For starters, it’s 421 pages.

Its bottom line:

This healthy dietary pattern for individuals ages 2 years and older is: (1) higher in vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, fish/seafood, and vegetable oils higher in unsaturated fat; and (2) lower in red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened foods and beverages, refined grains, and saturated fat. A healthy dietary pattern, as indicated by the systematic reviews, may also include consumption of fat-free or low-fat dairy and foods lower in sodium, and/or may include plant-based dietary options.

The proposed guidelines:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage. At every life stage—infancy, toddlerhood, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, pregnancy, lactation, and older adulthood—it is never too early or too late to eat healthfully.

- Customize and enjoy nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect personal preferences, cultural traditions, and budgetary considerations.

- Focus on meeting food group needs with nutrient-dense foods and beverages, and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit foods and beverages higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, and limit alcoholic beverages.

This looks like all the other Dietary Guidelines since 1980. Its bottom-line statement is more explicit than previously about reducing red meat and sugar-sweetened beverages.

Worth reading

- Support federal data. I especially appreciated the strong support for strengthening nutrition monitoring, food composition data (FoodData Central, an invaluable resource), and updating the Dietary Reference Intakes. Yes!

- The chapter on portion size. At last! Larger portions have more calories!

What’s missing

- A separate chapter on calories stated explicitly. The report discusses concerns about obesity and diet-related chronic disease in an excellent paragraph on page 1, and mentions calories but “stay within calorie limits” doesn’t get at what’s needed. I want more on “…adults and children [should] consume smaller portions of foods and beverages that are high in energy density and low in nutrient density.”

- A guideline to reduce consumption of ultra-processed foods. This committee, unwisely in my view, chose not to advise minimizing intake of ultra-processed foods, deeming their definition too uncertain and ignoring what are now three controlled clinical trials demonstrating that diets based on these food induce people to overconsume calories.

What’s confusing

–The addition of recommendations for diets in early childhood. This was done for the 2020-2025 guidelines and it involved doubling the size of the committee. This makes the committee’s work much harder and its report insufferably long. I would rather see a separate report on children (this could deal with the effects of food marketing as well).

–The health equity lens. I’m all for this but its discussion dominates the report. It is discussed in a separate chapter but then in boxes and other places throughout. The word “equity” is mentioned 217 times and “health equity lens” 38 times.

Although prior Committees incorporated basic demographic factors such as age, race, and ethnicity into their reviews of the science, this Committee considered additional factors and did so in a holistic manner as it reviewed, interpreted, and synthesized evidence across data analysis, systematic reviews, and food pattern modeling. In particular, this Committee considered factors that reflect social determinants of health (SDOH). In doing so, the Committee could interpret the evidence based on both demographic factors (which are considered to be downstream, i.e., more proximal in terms of their influence on behavior) and socioeconomic and political factors (which are considered to be upstream, i.e., broader societal factors that influence the distribution of power and resources). Addressing SDOH is considered key to achieving a just, equitable society.

Other comments

From the Meat Institute: Meat Institute Issues Statement on the Scientific Report of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee

“The Meat Institute remains strongly opposed to the Report’s recommendation to reduce meat consumption and will urge the agencies to reject it,” said Meat Institute President and CEO Julie Anna Potts.

From the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine: Prioritizing Plant-Based Protein in the Scientific Report of the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committee is a Step Forward, Doctors Say

For the first time, the advisory committee tasked with making scientific recommendations for revising the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended that the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines “include more nutrient-dense plant-based meal and dietary recommendation options,” prioritize plant-based protein over animal protein, and recognize the many benefits of beans, peas, and lentils as a protein source. The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) continued to discourage consuming foods like red meat, eggs, and dairy that are high in saturated fat, while also suggesting that the next Dietary Guidelines for Americans specifically recommend plain drinking water as the primary beverage for people to consume.

I can’t wait to see what comes next.

How to commennt

A 60-day public comment period on the Committee’s Scientific Report is open through February 10, 2025. More information about how to provide written and oral comments to the Departments is available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

- Read about opportunities to provide public comments, including requirements for oral comments

- Register to provide oral comments to the Departments. Note: do this now. Spaces are limited.

- Submit written public comments to the Departments

- Register to attend the virtual public meeting to hear oral comments on the Scientific Report

Read the Committee’s Scientific Report