I’m on the visionary panel. To register, click here.

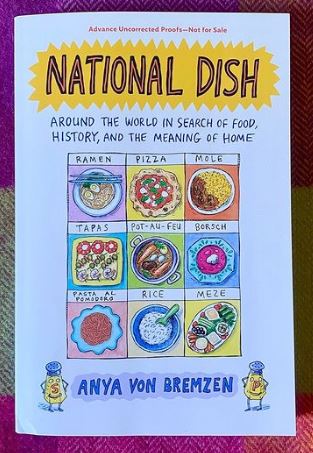

Anya Von Bremzen. History, and the Meaning of Home. Penguin, 2023.

I can never get over how many superb books are now published on food themes, on after another.

Consider—and you definitely should—this one, for example.

For starters, there’s the fabulous cover by Roz Chast, no less (I want one for my next book!).

For another, there’s its brilliant structure and what Von Bremzen does with it. She is a cookbook author, best known to me for her memoir, Masterian the Art of Soviet Cooking, an account of what food was like for a child growing up in Moscow in the former Soviet Union.

National Dish uses what are assumed to be foods representing entire cultures to reflect on the meaning of food for personal identity and larger issues of gastronationalism. Von Bremzen spent at least a month in each country examining how its particular dish did and did not represent the culture of Japan (Ramen noodles), France (Pot-au-Feu), Spain (tapas), and Mexico (mole), and others, necessarily ending with the most poignant, Ukraine (borsch).

Von Bremzen is great company on these explorations, delving into language, history, anthropology, and whatever else it takes to understsand the role of that particular food in that particular society. A couple of excerpts:

Neopolitans were not Italy’s original mangiamaccheroni, however; the Sicilians were. A twelfth-century Arab geographer, Muhammad al-Idrisi, was first to report that people near Palermo were making strings of dough called itriyya–-from the Arabic? Greek? Hebrew?—which they traded “by the shipload” to Calabria and “other Christian lands.” The Neopolitans? They were called mangiofoglie (leaf eaters), or, more quaintly, cacafoglie (leaf shitters) for their massive intake of dark leafy greens—a forerunner of the Brooklyn dream diet. (p. 52)

This, on “washoku—fuzzily defined as “the traditionally dietary cultures of the Japanese” and modeled on the equally fuzzy but successful “gastronomic meal of the French.”

But it was the UNESCO listing that produced a washoku explosion. A word only faintly known before to the Japanese public was now everywhere, celebrated in cookbooks, media articles, gastronomic guides, and scholarly studies. And the government—mixing bunka gaikō (cultural diplomacy and Brand Japan building—promoted washoku abroad as the nation’s ancient and healthy tradition. An upscale pizza effect swung into action. International recognition boosted washoku’s domestic cachet, swelling the pride that Japanest home cooks now took, according to polls, in their own intangible food heritage.

Intangible indeed. (p.103)

This is one terrific book, erudite but fun to read and a great contribution to the literature of food studies. Enjoy!