My monthly (first Sunday) Food Matters column in the San Francisco Chronicle is inspired by California’s petition initiative to get labeling of genetically modified foods on the ballot.

Q. I was just handed a petition for a ballot initiative to label genetically modified foods. I signed it, but how come GM foods aren’t already labeled?

A. Labeling GM foods should be a no-brainer. Practically everyone wants them labeled. That’s why the Committee for the Right to Know is collecting signatures for a California ballot initiative to require it.

To say that food biotechnology industry supporters oppose this idea is to understate the matter. They think the future of GM foods is at stake. They must believe that if the foods were labeled, nobody would buy them.

If consumers distrust GM foods, the industry has nobody to blame but itself. It has done little to inspire trust.

Labeling promotes trust. Not labeling is undemocratic; it does not allow choice.

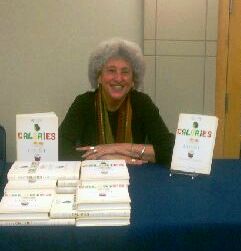

As I discuss in my book, “Safe Food,” I was a member of the FDA’s Food Advisory Committee when the agency approved production of the first GM tomato in 1994. As we learned later, the FDA was not asking our opinion. It was using us to gather reactions to decisions already made.

For reasons in part scientific but largely in response to industry pressures, the FDA decided that GM foods are inherently safe and no different from foods produced through traditional genetic techniques. Therefore, the thinking went, labeling would be unnecessary and mislead people into thinking that the foods are different and somehow inferior.

Some of us strongly advised the FDA to reconsider. We thought the issue of trust was paramount. If the products had some public benefit, people would buy them.

Consumers in Great Britain, for example, readily accepted tomato paste prominently labeled GM, not least because the cans were priced below those with conventional tomatoes.

But once Monsanto shipped GM corn to England without labeling it, and placed advertisements in British newspapers hyping the benefits of GM foods, the British public lost confidence. Sales declined and supermarket chains no longer were willing to carry GM items.

Today, close to 90 percent of corn, soybeans and sugar beets grown in the United States are GM varieties. You must assume that ingredients made from these foods are GM – unless the product is certified organic.

When researching “What to Eat,” I knew that Hawaiian papayas engineered to resist ringspot virus were the most likely candidates. I had some tested. The conventional was GM. The organic was not. Without labels, you have no way of knowing whether you are buying GM fruits and vegetables.

Intelligent people can argue about whether GM crops are good, bad or indifferent for agriculture, the environment and market economies, or whether the products are safe. But one point is clear. The absence of labeling cannot be good in the long run for business or American democracy.

Consumers have a right to know how foods are produced. Polls consistently report that most people want GM labeling. Lack of labeling raises uncomfortable questions about what the biotechnology industry and the FDA are trying to hide.

The FDA already requires labels to identify food that is made from concentrate or irradiated. At least 50 countries in Europe and elsewhere require disclosure of GM ingredients. I’ve seen candy bar labels in England with this statement: “Contains genetically modified sugar, soya and corn.” We could do this, too.

Last year, 14 states, including Oregon, New York and Vermont, introduced bills to require GM foods to be labeled. None passed, but the campaign has now gone national.

If you want a GM-label measure on the California ballot, go to labelgmos.org. Just Label It is still collecting signatures. Signing these petitions is an important way to exercise your democratic rights as a citizen.